Rock Island Armory 1911A2 DS, 9MM

Howdy, folks, and welcome back. Thank you for joining me for our recent series on the American service rifle, through many of its iterations.

For the next few weeks, I’ve got some “special guest stars” lined up, and I thought to use them as exemplars to discuss the various types of triggers available in modern pistols.

Of course, I just said modern, and now we’re going to start with a 1911. Sort of. In the never ending controversy between the Glock-boys and the 1911 traditionalists, it’s always the originals, the double stack 9MM Glock, vs the single stack .45 ACP 1911. As such the argument usually hinges on caliber effectiveness and capacity (and the meme of 1911s that jam,) more than any of the other virtues and vices of the two platforms.

In this case, the 1911 is a double stack 9MM, so they are on equal footing, for once. Let’s instead look at the trigger system. This one is a Rock Island Armory, an up-market version of the budget gun made in the Phillipines, which my dad picked up when he wanted a highly shootable high-cap for 3-gun purposes. Before the present embarrassment of riches in budget friendly 2011s, (the Tisas version is under 500 bones, these days. That’s a third of what STIs were going for when Dad got this one, and less than a fifth of what Staccatos bring nowadays,) the double stack Rock was one of the better choices available. It’s built more or less on the old Para-Ordnance style, and initially used Para pattern magazines. The problem at the time was that although Para mags were cheaper than STI-style, they were just about non-existent. Fortunately, by modifying the mag release, it could be adapted to use the STIs.

The 1911 is famous for several things, but possibly its greatest virtue is its single action only trigger system. That trigger is what’s made it the foundation for the vast majority of race-guns. That trigger is largely what’s kept it relevant over a hundred years after its inception.

The best way to look at the different triggers and how they work is to consider how much energy it takes to set off a cartridge primer. It takes a good sharp blow to do it, and the way we’ve developed to deliver that blow is by loading a spring. Picture loading that spring as pushing a rock up a hill. In a Single Action system, rolling the rock is represented by cocking the hammer. The rock sits, teetering at the top of the hill with a wedge under it. You’ve got a rope tied to the wedge. All you’ve got to do is yank on the rope and the rock starts to roll.

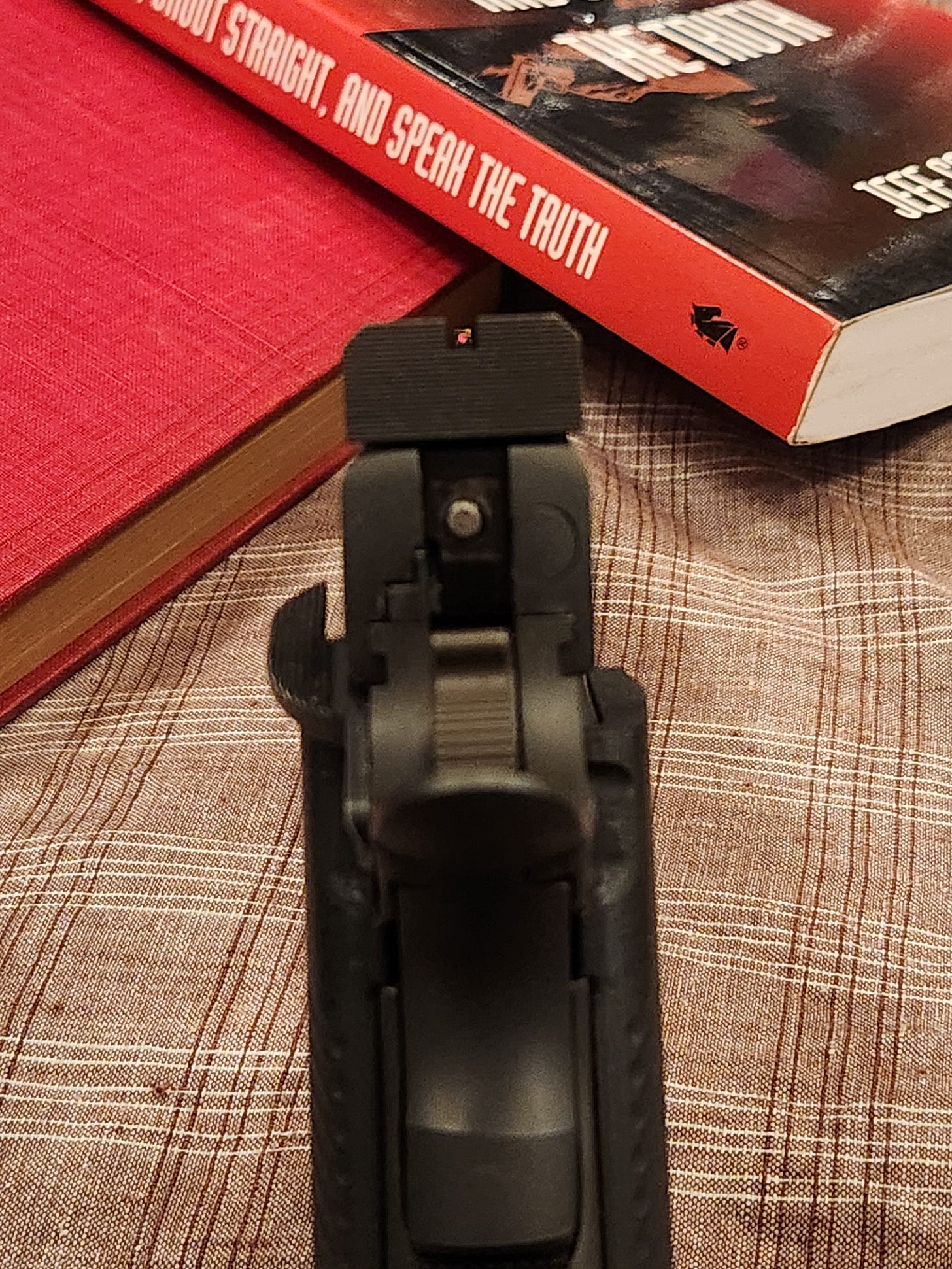

What makes the 1911’s trigger so unique is that rather than being hinged at the top, like almost all others, it slides straight backward. With proper fitting, the pull can be extremely light and crisp, with hardly any perceptible movement when it breaks. Reset is equally short, making for an extremely fast system with hardly any excess movement to control for. It’s a Single Action Only system, meaning the hammer has to be cocked before it can fire. With the hammer down, you can yank on it all day and get no bang. (Think about that the next time you see a 1911 aimed at someone in a movie standoff, and five minutes in, they cock the gun for dramatic effect. What were they gonna do if the baddie made a break before that? Stand there looking silly?)

The downside to a light, crisp trigger is usually safety. If it’s easy to set it off when you want to, it’s probably easy to set off when you don’t, as well. In the case of the 1911, the second part of its brilliance are its safeties. It has two: a grip safety and a thumb safety. The grip safety has to be depressed by having an adequate grip on the gun, otherwise it blocks the trigger bow from moving.

The thumb safety blocks the sear, the part that when pressed by the trigger bow, actually releases the hammer. Two different safeties, acting on different parts of the mechanism make it almost impossible1.

With those safeties in place, the gun is safe to carry cocked, (meaning hammer back in firing position,) and locked, (meaning with the safeties on.) This gives the best of both worlds, an extremely safe gun when it’s “switched off,” but which can be “switched on” at a moment’s notice, ready to go with the world’s best trigger.

There are downsides, of course. There always are. “But what if I forget to take the safety off in the heat of the moment?” “Uh… excuse me, sir. Did you know your gun is cocked? That’s really scary.” And last but not least:

The first and the last are both training issues. Train until the safety comes off automatically as part of the draw stroke. Train to keep your finger off that excellent trigger until you’re ready to shoot.

That middle one though is much harder to address, at least in an agency context. Law enforcers typically have to be seen to be armed, yet don’t want to appear so aggressive that they’re walking around with cocked handguns, ready to go off with a “hair trigger.” It’s a bad optic, as they say. And it’s the agency context that drives most pistol development. Since it’s hard to educate the entire public about the desirability of washing their hands, let alone the proper operation of a semi-automatic handgun, there have been a number of solutions to that “problem” over the years.

Make sure to subscribe so as not to miss next week’s post, when we look at the first major answer: the DA/SA.

since I am here singing the praises of the 1911 system, I won’t get into the Series 80 and its firing pin block. Suffice to say that there are ways to skin that cat without a bunch of extra gobbledy-gook befouling the world’s finest trigger.

Since I’m often in a graphical mood, I’m envisioning a chart with the x-axis showing “timing of consequences,” & the y-axis showing “severity of consequences.” No handwashing would be in the top right corner of this graph. Poor firearms safety habits would be in the top left hand corner. Please feel free to plot other points.

Great write up. With all due respect, 1911 chambered in 9mm is sacrilegious.