Shooting Wax

Today’s article will be a bit of a departure, as I don’t have a gun lined up to write about. Instead, I’d like to share an old school practice and training technique that folks might find useful today.

Making and shooting wax bullets.

I first encountered this technique watching archival footage of the late great Border Patrol man, Bill Jordan, doing exhibition shooting. He had a number of impressive tricks, such as holding a ping pong ball waist high on the back of his hand, waist high, then drawing with the same hand, and shooting the ball before it hit the ground. Shooting an aspirin off a table, from the hip.

But possibly the most impressive part of all that? He was doing it in front of a studio audience, not out in a field somewhere. No major investment in backstops, no specially constructed buildings, not even any earmuffs. Just blasting away. Impressive marksmanship, no casualties. How did he do it? Wax bullets. How did he afford to train to that level? Wax bullets. Primer only, no powder need apply.

There’s a lot you can do even cheaper than wax, with plain old dry-fire. It’s free. Even with a gun with a delicate firing pin like my Charter Bulldog, snap-caps are cheap. Dry fire is a phenomenal tool for learning a double action trigger, for learning how to transition between targets and other skills. It takes focus, and it takes self honesty to assess the sight picture you just saw. If you’re a good observer and honest with yourself, you know where that shot broke.

What dry fire can’t tell you about is unsighted fire. Point shooting. Hip shooting. Fast draw. Without a sight picture to be honest about, you don’t know where that shot went. It’s also not really something most folks ought to jump into trying with live ammunition, for the same reason. You don’t know where that bullet’s gonna go.

Load up with wax bullets, however, and you can find out quickly and safely. They can punch holes in cardboard targets or knock over soda cans, but probably won’t leave a gaping hole in your leg in case of an “oops.”

They’re also great for general practice. In your basement, on the porch, lots of places you might not be set up for real ammunition, you can fire wax.

Since they have little noise (just enough to trigger a shot timer, happily enough,) and almost no recoil, they’re fantastic training aids for new shooters, too. They do tend to be more revolver oriented, as a revolver can cycle right through a cylinder without recoil, no problem. They can be used in a semi-auto, but it becomes essentially a bolt action. Good for working out of the holster, for example, but not much on the follow up shots.

Ok, Type-Writin’ Trucker, you say. I’m sold. Wax sounds awesome. How do I do it?

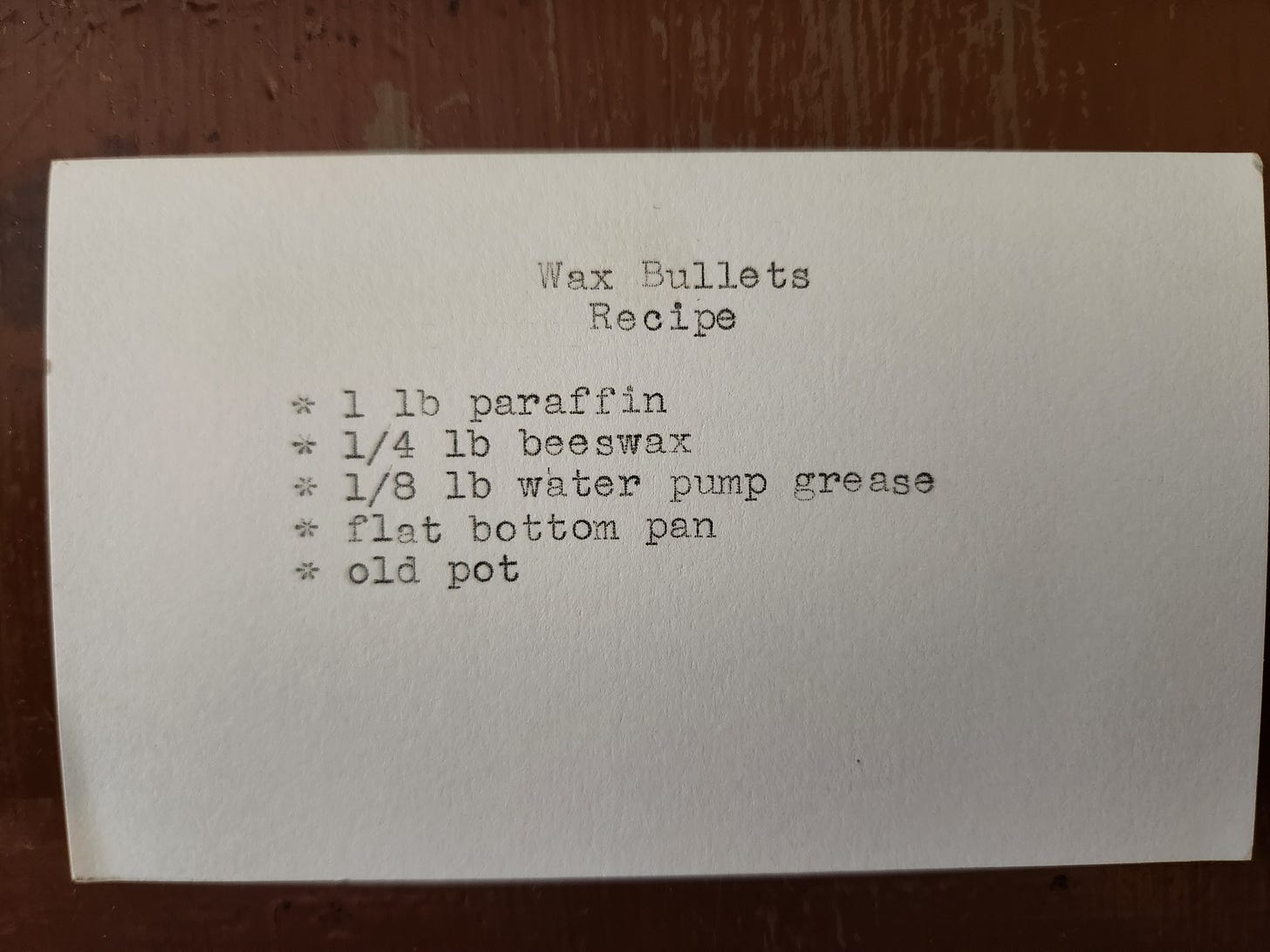

Well, that’s something of a lost art. I found a recipe that dates back to the 42nd Lyman Reloading Handbook, from 1960.

The combination of the paraffin and beeswax is softer and more flexible than straight paraffin, and the grease helps it get down the bore without making a mess.

Combine the paraffin and beeswax in the old pot. Some people recommend a double boiler for this step, as the mixture can be flammable if overheated, or exposed to flame. Once the waxes have liquefied, carefully add the grease. (I used “Lubriplate No. 115.”) Stir gently until the grease unclumps and blends with the wax. Pour into the flat bottom pan. About half an inch deep for .38s, add an eighth or so for .44s. Place on a level surface where it won’t be disturbed while it cools, lest you get ridges. Ruffles are great for potato chips, less so for consistent bullets.

While that’s cooling, you can prepare the cases. Resize and decap as usual, but then you’ll need to enlarge the flash hole. The standard size will back the primer out and bind the cylinder. With a normal lead and powder load, the recoil is enough to force the case back against the recoil shield, and reseat the primer, but with no recoil to speak of, that won’t happen here. So chuck up a 1/8th in drill bit, and open them up a bit. Then mark them as dedicated for wax only, as an oversized flash hole is a good way to start too much propellant burning at once and lead to an overpressure situation in a normal load.

Once the wax has cooled, turn it out on a hard, flat, clean surface. Push the mouth of the cases in like a cookie cutter. It’ll cut out the disk of wax, then just pull it out. Sometimes it’ll leave some residue on the outside of the case, just wipe it off with a rag, or enlist a helper to do that bit.

Once the wax is seated, then prime the cases. If you prime first and then wax, the trapped and pressurized air will push the wax back out. Priming second has no such issue.

Now do that again 50 or 100 times, and you’re ready for some wax bullet fun.

In a .38 Special, these bullets weigh about 7 grains. With a primer only, they’re good for 450-500 fps at the muzzle, which makes for a whopping 3.5 ft lbs of muzzle energy. Pretty nearly anything solid with stop them, or they’ll just get tired and fall out of the air fairly soon. If you really want to be budget conscious, an old bed sheet hung up behind the target will catch them, and you can re-use the wax. Just be careful to keep it clean.

Have fun!

Used them for years for revolver practice following the great Bill Jordan's recipe. Only stopped after I quit competing in revolver matches. Article makes me miss all the fun I used to have. Gonna have to work up a batch. Thanks

Interesting that you refer to the Charter Arms firing pin as “delicate.” I recall that back in the 1970s, Charter Arms used to make quite a big deal over their indestructible beryllium copper firing pins. Did they start making the firing pins out of something else?