Charter Arms Bulldog .44 Spl

Howdy folks, and welcome back to Tales of a Gun. This week, we'll be looking at my latest firearm with a round thingy in the middle, the Charter Arms Bulldog, in .44 Special.

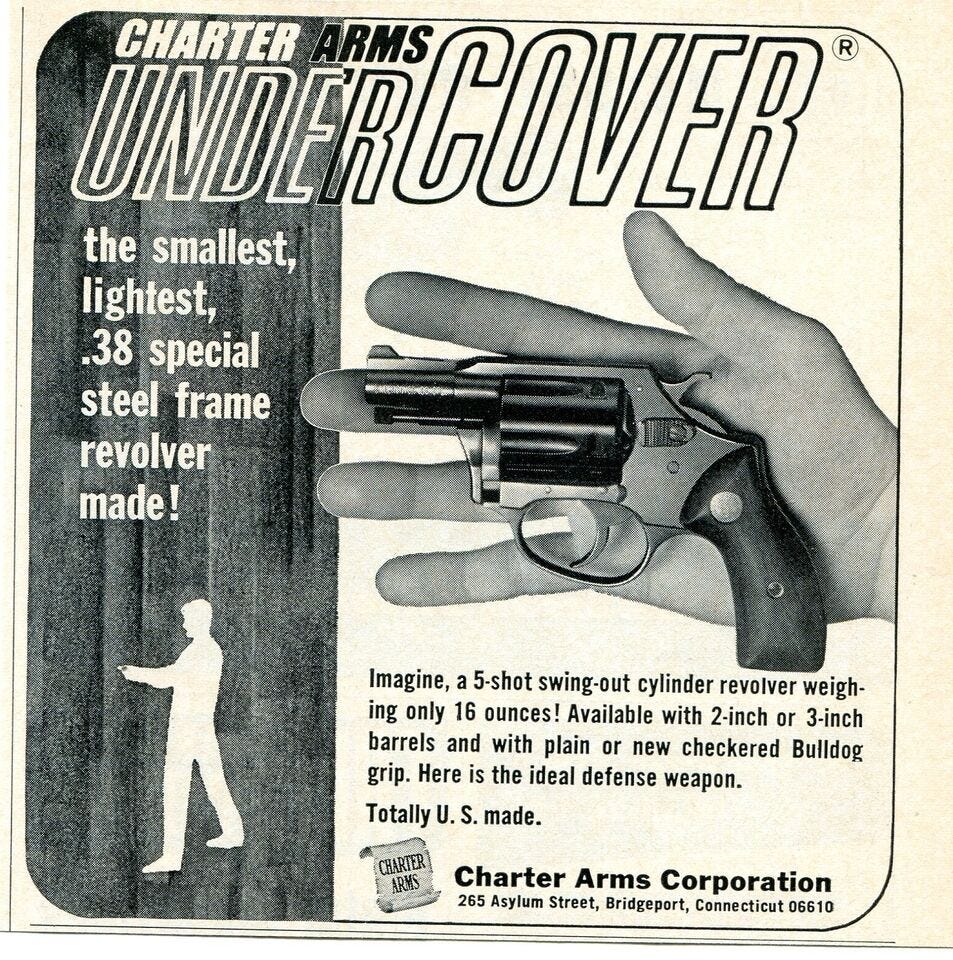

First, you may ask, who the heck are Charter Arms? They are a relative latecomer to the American gunmaking scene, being founded in 1964. Over a hundred years younger than Remington, Smith & Wesson or Colt, younger even than Ruger. In fact the company's founder, Douglas McClenahan, was an alumnus of both Colt and Ruger, as well as High Standard, by the time he decided to go out on his own.

He took what he had learned and designed his own revolver. One with a number of interesting departures from the older, established brands with their older, established models. We'll look closer at some of those innovations in a bit. He also settled in Bridgeport, CT, at a time when New England still teemed with experienced and expert machinists, before the unfavorable climate started pushing companies out.

Being privately held, the company has had a rocky road. Douglas brought on a partner in the late '60s, then retired for health reasons in the late '70s. The partner ran it for a while, and brought his son on board. Some investors bought it, then it went bankrupt and closed. Then the partner's son brought it back around the turn of the century. They seem to have steadied down through the 2010s and are still cranking out Charters today. They are still based in Connecticut, and interestingly for an American company, still competitive in price with the bargain imports from Brazil or the Phillipines. One can typically buy two or three Charter Arms for the price of one revolver from Colt, Smith, or Ruger.

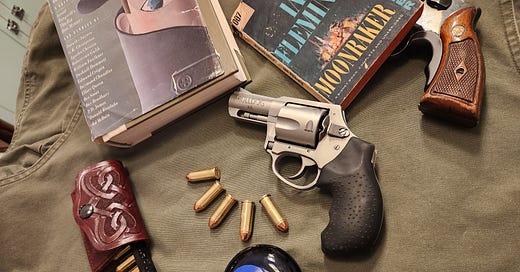

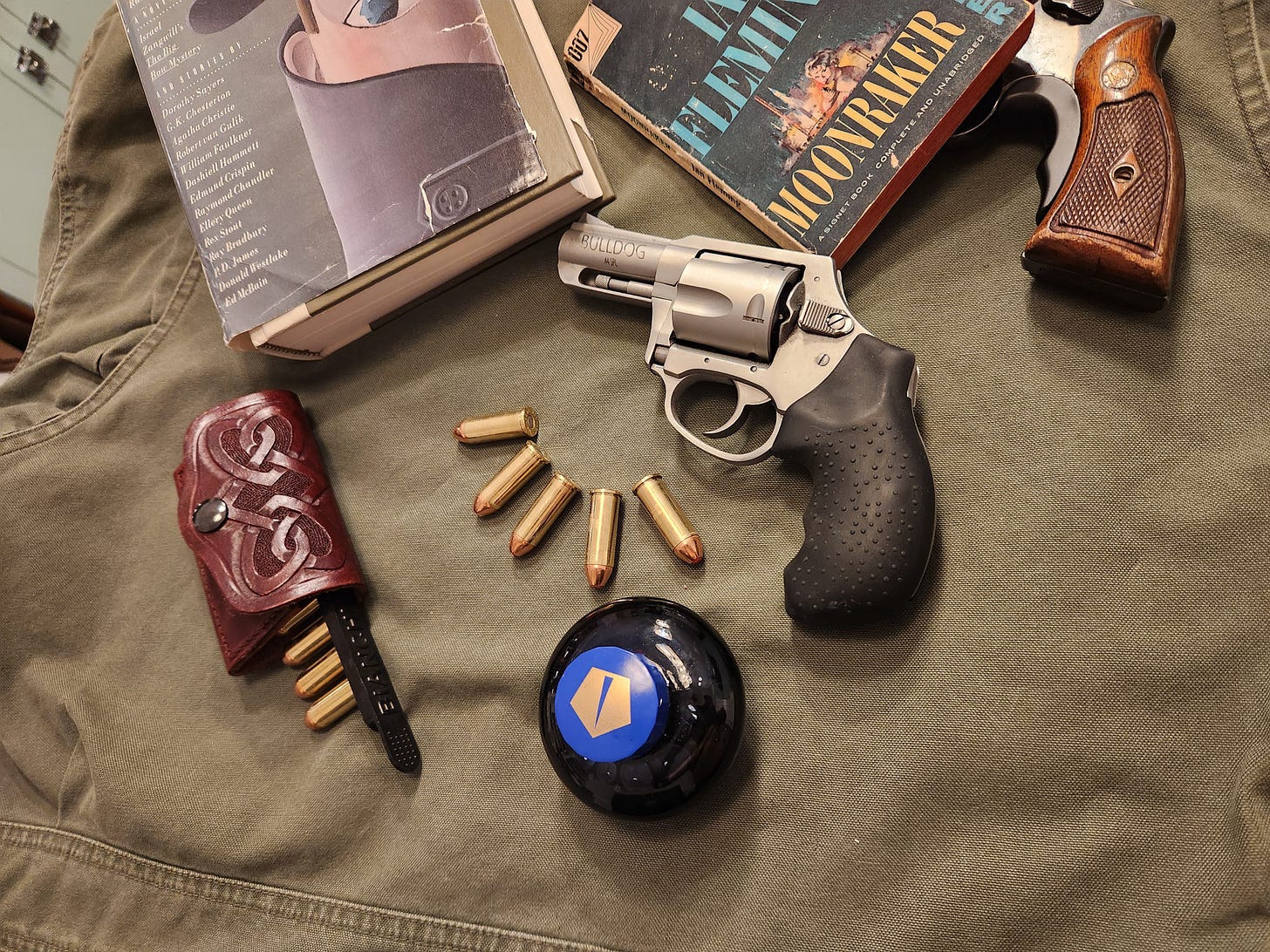

That out of the way, what's a Bulldog? Named in honor of the old British Bulldog revolvers, short nosed guns, (like their animal namesake,) which favored a big heavy bullet traveling quite slowly, the Charter Bulldog is a big-bore snubby. It carries five rounds of .44 Special, the now somewhat obscure predecessor to .44 Magnum, in a package smaller (and a LOT lighter) than a Smith K-frame. A lot of reviewers will claim that "it's not much bigger than a j-frame!"

Well, maybe not, but it's enough bigger that it's a different sort of beast. The J is small enough to fit in a trouser pocket. People stick them all sorts of places. The Bulldog, unless you've got serious Captain Kangaroo pockets, is just enough too big for that, IMO. It's great as a light belt gun, though. I carry mine AIWB, and after carrying the Model 10 that way for a few months, barely notice this one. Its workable as a coat pocket carry, but a J-frame would still be better for that context.

How did this sorcery occur? That's part of what makes the Charter so interesting. Both Smith and Colt designs have the entire frame, from where the barrel screws in at the front, around the cylinder window, and down to the bottom of the grip all made of one piece of steel. In order to get the lockwork in and out, that steel frame is essentially single sided. A removable sideplate covers the lockwork, but doesn't add materially to the design's strength. The frame, therefore, has to be thick enough to support the cylinder and contain the firing forces, with just the metal on that one side.

McClenahan, on the other hand, seems to have borrowed from the Ruger single actions. He made his frame double sided, and thus much stronger, even though it's thinner (and thus lighter.) Instead of the sideplate being removable, the grip frame comes off with a couple of pins. The action parts can then be removed through the bottom.

That also allowed for the grip frame to be made of a different metal, as it doesn't need the strength of steel. Aluminum is perfectly adequate there.

That does necessitate some compromises, however. The cylinder hand and bolt are both quite thin pieces of metal, which raises questions of their durability. The cylinder crane and ejection rod, presumably in an effort to reduce parts count and cylinder size, do not have a fixed sleeve for the rod to travel in. As a result, any sideways force applied to the cylinder during unloading will often bind the ejection rod

.

My example is a current production model in stainless steel.

The barrel is 2.5", with both a top rib and underlug/ejection rod shroud. Personally, I'd prefer a lighter contour barrel. If the goal is light weight, after all, why add the ballast?

It is double action only, with a bobbed hammer. I would prefer an enclosed hammer, like on the Centennial model Smiths, but they don't offer one. This one can't really do the fire from inside the coat pocket trick, as the hammer will often foul on the pocket lining.

It's been something of a project getting this thing ironed out. When I first got it, the timing was off, causing the action to be glitchy. The hand started trying to push the cylinder around before the bolt had yet dropped to release it.

As a former competition shooter, I'm prone to dry fire my guns. A lot. I've never really had trouble with Smiths or Rugers, and had mostly put all the "oh noes! Never dry fire a gun! It's bad for it!" stuff one hears down as an old wive's tale. In this case, however, some caution may have been warranted. I was dry firing at a paper "target," and heard a slap. The only thing that could really have been was the firing pin. I checked it, and sure enough, with the hammer down and trigger pulled, there was no protrusion. A quick search found the missing offender.

A quick note to Charter's customer service had a new pin on its way. They offered to repair the gun if I sent it in, but I figured I could do it faster.

I figured wrong, because I promptly chickened out at pulling all the pins and disassembling the Charter's unusual action. It sat in the safe with the new part taped to it for a month or more, before I finally decided to take it to a 'smith. Fortunately, we've got one in the family, and they got it, as well as the timing issue, taken care of.

The other issue I've had with it recently is the factory rubber grips. In addition to the sins of all rubber grips, (i.e., they stick to clothing, causing printing when the cover garment doesn't flow and drape properly, and can even try to drag the gun out of the holster,) these are only rubber, with nothing to stiffen them. Even the nut the grip screw threads into is only a press fit in the opposite side panel. These things are floppy. I can pull them off by hand. In fact a couple of times when handling the gun with gloves, they've actually come off accidentally.

I'm trying to find a solution. I picked up a set of vintage wood grips. They fit perfectly, but didn't come with a screw. I haven't managed to source one, yet. I'm also looking at aftermarket options, but haven't clicked "buy now" on any of them, yet.

All in all, most guns take some fiddling to get them dialed in, but this one seems to be taking more than most. However, that magic form factor, .44 firepower in a small and above all, light package is enough to keep me tinkering.

How about you? Do you have any promising guns that took some effort to make work?

I have a charter arms .44spl bulldog. Bought it in '87 or '88. Carried it for years inside the belt, behind the back. I did replace the grips with Packmeyer (sp) grips however. Made a difference in handling, IMHO, but it was what all of the folks shooting those (that I used to know) went to.

I was always amazed at how accurate it was.

These days however i don't carry or shoot it (much) anymore. The lack of .44spl rounds on the market makes it quite expensive, and those are all pretty heavy loads, so it kicks like a mule.

I don't like bobbed or hidden hammers on my revolvers, as I like the ability of being able to cock it when I need the accuracy of the lighter trigger pull.

Mine has also never had a problem and was in perfect working order back when I bought it.