How to choose a pistol

Howdy, folks, and welcome back to Type-Writin’ Trucker’s Monday Gunday edition. This week will be a bit of a change of pace. I don’t really have a gun lined up to write about, but I do have a head full of thoughts on this topic. Several people in my life are either coming back to carrying, or leaning toward starting. As such, I’ve been thinking this one through. A number of the points here I’ve already discussed at greater length in earlier articles, but this will be something of a synthesis.

My (somewhat flip) answer for a long time has been “get a Glock 19, a case of ammo, and a good class. With some training and experience under your belt, you’ll have a better idea what you want and what you’re looking at.” I still don’t think that’s bad advice, although there is a safety issue with striker-fired guns.

Another approach that’s frequently recommended is “go rent a bunch of guns, and see which one you like.” This one has some pros and cons. On the positive side of the ledger is that people are individuals. Hand shapes, strength levels, body types, and even aesthetic tastes vary widely. Picking out a gun for someone else is like buying underwear. It’s kinda personal. Like produce at the supermarket, you wanna pick your own. The downside is that for the average newcomer who hasn’t been trained in grip, trigger control, sight picture and all the rest, the rental case is like the first time you bought avocados. You just don’t know what you’re looking for.

Another point against it is that if you go into a gun shop looking for a carry gun, the good people behind the counter are likely to steer you toward the carry guns. Makes sense, right? The problem is that we’ve made such strides in the last thirty years, that carry guns are lighter, more compact and more powerful than ever before. We truly live in a golden age of portable firepower.

That sounds like a good thing. The downside with light, compact, powerful pistols—like so many of today’s 9MM pocket rockets—is that they are a bear to shoot well. In the world of packin’ pistols, everything is a compromise. Thanks to Sir Isaac and that pesky Third Law, every action has an equal and opposite reaction. With little mass to soak up the energy, light and powerful means a powerful recoil, as well. Compact tends to mean a short grip, harder to get a hold of. Short barreled means an unforgivingly short sight radius.

All of that is manageable for an experienced shooter, but it makes for one heck of a steep learning curve for a beginner.

So. An approach:

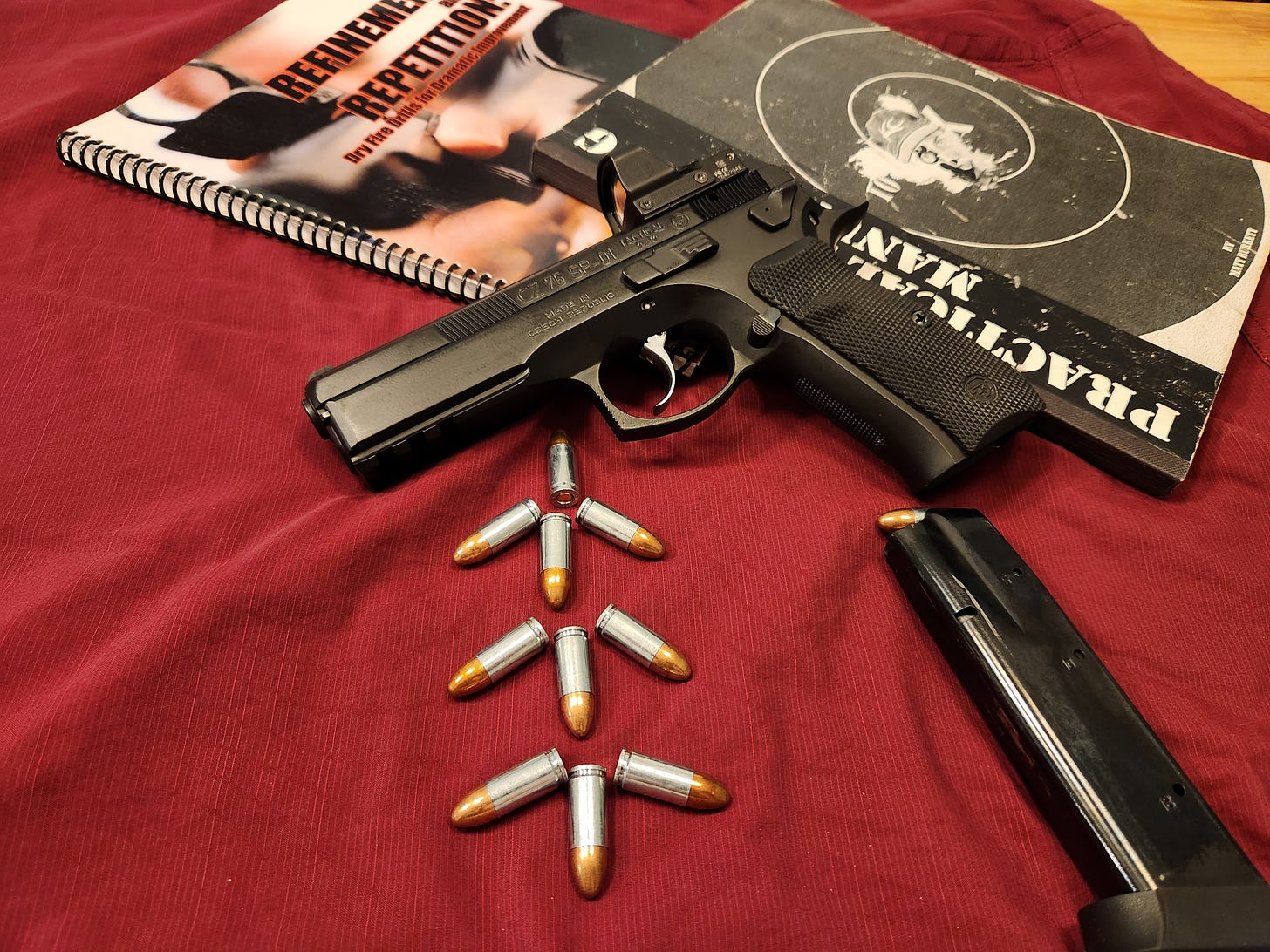

This may seem counter-intuitive: if you want a carry gun, go shopping for a service pistol. A full size gun will turn that fire-breathing monster of a full power service cartridge into a fairly tame housecat. 9MM may be rugged in a 16 oz pocket pistol, but is downright mousy when launched from 40 oz of stainless steel. A couple of added bonuses: this approach culls the field of a lot of the questionable bargains at the bottom of the market, as well as the rarefied boutique stuff at the top. Service pistols tend to be well designed and thoroughly tested. Many of the major designs are available second hand as “law-enforcement trade ins.” When agencies trade in, (what seems like every couple of years,) their guns often have significant cosmetic wear from the holster, but cops don’t actually shoot that much. A few hundred rounds a year for qualifications and practice is normal, but the guns can last for tens of thousands. This can save 50-75% over a new one, hopefully easing the bite of the “buy two guns” approach.

Use that gun as a learning tool. Handily, a full size service pistol makes a dandy competition platform in gun games like USPSA or IDPA. Once you’ve got some fundamentals down on the square range, there’s not really a better way to really learn.

Then, since all the major designs are available in a range of sizes, usually full size, compact, sub-compact, and micro, and a variety of calibers, it should be easy to find its little brother. All the skills you’ve built on the big gun transfer pretty readily to the little one.

Now, which service pistol? Well, here we’re back to that “buying other people’s underwear,” idea. But, I’ll summarize the basics of what you’ll see in the rental case:

Action types: Each has its pros and cons.

Single Action Only (SAO): Mostly found in legacy designs like the 1911 or Browning Hi-Power, or their derivatives. The trigger only performs a single action, it releases the hammer, firing the shot. This is the platonic ideal of a trigger, light, short and crisp, but it comes at the expense of one or more manual safeties which must be defeated before it can fire. That takes training, and even top flight shooters can still fumble occasionally. Light and crisp allows very fine shooting, but uses fine motor skills which may degrade under stress.

Double Action Only (DAO): The trigger performs two actions in one longer, heavier pull: first cocking, then releasing the hammer. This is common with defensive revolvers, and is occasionally seen in auto-loaders. The heavy trigger is all the safety that’s needed, there’s usually no manual one. It takes significant practice to shoot a DA trigger well, but is doable. Trigger is consistent from shot to shot.

Double Action/Single Action (DA/SA): Double action for the first shot, but then single action for subsequent shots. Usually no safety to defeat, but two trigger types to master, and the transition from first to second shot can cause issues.

Striker Fired: Probably the most common system today. Essentially a midpoint between SAO and DAO. Same trigger pull throughout, lighter and shorter than DAO, but longer and heavier than SAO. Usually no manual safety, but trigger might not be heavy enough to qualify as a safety on its own. Can present safety issues, though these can be overcome with training or modification.

Materials: the slide is always made of steel, but the frame can vary.

Steel: heavy, usually more expensive to produce. Usually found in older designs. Excellent for the full size trainer gun, less so for schlepping around all day. Blued steel is prone to rust if not kept oiled. Stainless does just what it says on the label: it stains less. With sufficient abuse it can still rust, but nothing like blued steel. The modern finishes improve on this drastically.

Aluminum: lighter than steel, usually equivalent to or slightly heavier than polymer. Often found in carry-optimized versions of older steel models. Sometimes found as a standalone design, sometimes as a premium option for a polymer model.

Polymer: most common option. Today’s plastics are incredibly tough and durable. Cheap to produce. Flexes slightly under recoil, which provides a slight cushioning effect. Polymer guns may not recoil as badly as their light weight would suggest.

Closing thoughts: common, current production models are the easiest to find, find parts (like magazines and springs,) and holsters for. That doesn’t mean older models are impossible, but it’s the difference between finding the model you want at the local shop, or special ordering it. “Custom orders may take 6-8 weeks to arrive.”

Controversial: The elephant in the room right now is SIG Sauer. Their P365 and its variants are presently at the top of the heap of carry guns. The various makers had been focusing on smaller and smaller guns, sacrificing capacity. The Glock 43 only holds 6, for example, then the P365 came out, managing to fit 10 rounds in a very similar footprint. Sales went bananas but quality slipped. Also, the closest thing to a service pistol version is the Sig P320, currently the center of its own firestorm due to reports of “uncommanded discharges,” i.e. going off in the holster with nothing contacting the trigger. Popular as they may be, I don’t think I’ll buy one anytime soon.

Finally, (really! I mean it this time!) revolvers. This is another controversial topic, but I’ll see if I can thread the needle. Revolvers are often suggested as good guns for non-shooters. There are some good reasons for that. They are simple to use. Just swing out the cylinder, fill up the holes with bullets, close it up, pull the trigger as needed. Rinse and repeat. They tend to tolerate neglect better than auto-loaders. However, they are just as often viewed as terrible advice, given by people who don’t know their earhole from their elbow. After all, a 12 pound DA trigger takes a lot of work to master, work that probably won’t be put in by non-shooters. Add that to the tiny sights and short sight radius of the typical defensive snub-nose, and you’ve got a very difficult combination, not new shooter friendly.

If, however, one was to follow the program above, buying a medium or large frame revolver first, then following it up with the snubby, there are significant benefits to be gained. Round guns tend to be reliable. Round guns are often less uncomfortable than planes and angles when strapped to a round body. With no slide to be forced out of battery, they can be fired in contact with the target, and on concealed hammer models they can be fired within a pocket. (And significant limitations. Only 5 or 6 rounds on board. Reloads are slow and fiddly. If a revolver does jam up, it’s much harder to fix short of a gunsmith’s bench.)

Happy shooting, and stay safe everyone.

Good article. I tend to split the difference. I suggest the person go rent a Glock 19 (most generic gun you can find) and shoot 100-200 rounds. Make a written list of what he/she likes and dislikes about it, from shooting to handling to hand fit to budget to everything. Then, get with a knowledgeable gun seller (or smart friend) and use the list to find a gun that meets the preference. It's like buying a car in that aspect.

For a brand-new shooter, I'm not above recommending a .22lr pistol as a starting point. The round will do the job for self-defense, and the ammo price and enjoyability encourages practice.

Good general summary. You might provide some more context to the safety issue of striker-fired guns so that new shooters will understand they’ll be fine with a striker if they learn to manage the trigger finger correctly. Maybe a topic for a future article?