1836 Colt Paterson

Howdy, folks. Welcome to Monday, where we all wish it was Gun Day. That’s our Fun Day. Before we get into today’s article, a few notes on the direction of this Substack. I started this by just going through guns I own, as I tend to have a lot of experience with them, and they’re readily available for photography. I’ve pretty much reached the end of the interesting guns in my safe, as well as those readily borrowable to review. Going forward, my thought is for articles on more historical guns, interspersed with the occasional new gun review, (I’ve got a potential source for access to T&E guns, but comparing which new release holds one extra round or is half an ounce lighter this year isn’t exactly my driving passion in writing about guns,) along with some more technique oriented posts, both on high performance shooting and the practical aspects of CCW. Hopefully, there will also be some training and competition writeups as well. (Time, time! Ask me for anything but time!)

I like shooting pretty pictures of guns almost as much as I enjoy shooting guns, or writing informative snark about them. I’ll do my best to get good photography, but there are likely to be more stock photos as well. It’s the nature of the beast with guns I don’t own.

All that having been said, let’s dive in:

The 1836 Colt Paterson revolver. “The what?” I hear you ask. “You’re getting pretty obscure here, Jesse.” You look at the picture. After all, that’s what it’s there for. Help jump start reader’s memories. “Hey, I remember that one! It was in such-and-such movie, starring so-and-so!” Even then, this one’s pretty obscure, since it just doesn’t look the part. The biggest exception I found in a quick check of IMFDB, (invaluable resource, that,) was Supernatural, where it is featured as “The Colt.”

More likely, you’re probably asking “What happened to that poor gun? It looks like something’s missing. Kinda… I dunno, oddly misshapen, too.”

This is, as I mentioned at the top, the Colt Paterson revolver, as introduced in 1836, thirty-seven years before its famous descendant*, the Colt Peacemaker of 1873. What makes it significant enough for us to look at, is that it’s the first commercially produced revolver. It’s the cornerstone of a firm that would go on to give us many of the most iconic firearms of two centuries.

Before Sam Colt and this funky, half baked forerunner came on the scene, the vast majority of pistols were single shot, muzzle loading affairs.

For several centuries, this led to fighting with a sword in the right hand, a pistol held in reserve in the left. If you wanted more shots, you carried a brace (pair) or more of pistols.

Edward Teach, known professionally as the pirate Blackbeard, was one who favored this approach, reportedly carrying as many as six pistols. (And some burning cannon fuse stuck in his hat, just for the effect.) A backup gun is not a terrible idea even today, but six is probably excessive. (As is the lit slow match. You can buy “Gun Smoke” scented soap, but smoking indoors will seriously limit your social life these days.)

There had been a number of attempts to build multi-shot firearms, but most were strange, cumbersome beasts to today’s eyes. There were multiple barrels, like a side-by-side shotgun, or even more. Since anything worth doing is worth overdoing, this sometimes resulted in more barrels than Blackbeard carried pistols. The Joseph Manton 18 barrel pepperbox is a prime example.

The ignition system was a major stumbling block in the early days of repeating firearms. Human ingenuity being what it is, there were in fact several early revolvers. One such from 1580, was a matchlock, with a separate pan for each chamber which rotated along with them.

Another was a self metering design which fed the pan from a powder reservoir each time the hammer was cocked. As with many early firearms, a lot of things have to go right for that to work out. To quote Rooster Cogburn: “I got me a .22 pepperbox here. This thing shoots five times, sometimes all at once.”

Most of the pepperboxes required rotating that big block of barrels by hand, as well. Less cumbersome than pouring powder and ball for a single shot, of course, but hardly ideal. The big block of barrels was another fly in the ointment. For pistol, designed for portable personal protection, redundant components tend to decrease the portability drastically.

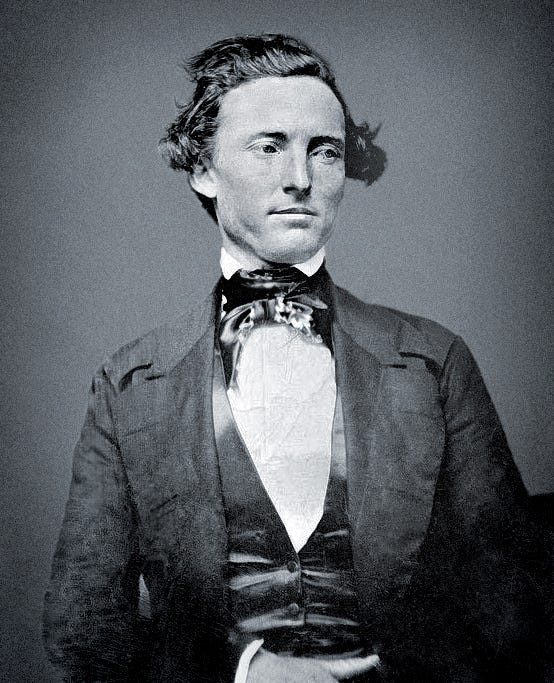

Such was the state of the market when Our Lad, Sam Colt took passage on the brig Corvo, bound for Calcutta. He’d been sent to sea as an apprentice seaman after an explosion from one of his pyrotechnic projects nearly destroyed his boarding house. One presumes the voyage taught the young man many things, but the most notable to posterity resulted from the consideration of the ratcheting pawl mechanism that controlled the windlasses and capstan of the ship.

While still on board, he managed to build a wooden mockup of a pepperbox type pistol, but with a barrel block that roatated automatically when the hammer was cocked, and locked in place with a barrel in line, both vast improvements on the earlier system.

When he returned to the states, he borrowed some funds from his father to work on the design. He hired a gunsmith to build a rifle and pistol along the lines he’d thought out aboard ship. Ironically, the rifle performed well, but the pistol exploded in testing. When his father refused to put up anymore money, young Sam tried a variety of other ways to make money, including as a traveling “medicine man,” giving demonstrations of nitrous oxide, better known as laughing gas. The public speaking skills he honed in his patent medicine period stood him in good stead later, selling pistols to governments around the world.

Meanwhile, once he had built up some capital, along with a loan from Henry Ellsworth, a friend of his father, he began work with the gunsmith John Pearson, developing his idea. Here the multiple barrel design of the pepperbox fell away, leaving multiple chambers rotating behind a single fixed barrel. This made, of course for a significantly lighter pistol. The development took several years, but in 1835, he was ready to patent the new gun.

Ironically, by this time the head of the US Patent Office was Henry Ellsworth, friend of the Colt Family and Sam’s early investor. Ellsworth advised that he first file his patents in England, as a prior American patent would make him ineligible for one in Britain. Thus the first patent for the Colt Revolver, most American of weapons, is British.

On his return he put his sales skills to good use, raising money from investors, and forming a corporation of venture capitalists to get the new idea to market. Much like in writing, good ideas are easy, promoting them is hard. By 1836, at the age of 22, he was ready. The Patent Arms Manufacturing Company was chartered in Paterson, New Jersey. He was paid a royalty for each gun produced according to said patent. Fortunately for him, it was also stipulated that the patent rights reverted to him in the event of the corporation’s dissolution.

Thus was born the Paterson revolver. It might not have been the first revolving pistol, but it was the first to lock the chamber in alignment with the barrel, and percussion caps greatly improved ignition over the old rock locks. His greatest contribution was in how the revolvers were produced. On the forefront of the industrial revolution, he pioneered the use of interchangeable parts and the assembly line.

The gun itself, as initially produced, held five rounds. The barrel was 7.5”, was rifled, and bored to fire a 0.28 caliber lead ball. There was no loading lever, the barrel and cylinder would have to be removed to allow charging. Black powder would be poured into each chamber, then lead balls pressed into place with a separate lever tool, or simply the arbor pin as field expedient.

The biggest thing missing to modern eyes is the trigger guard. Rather than a fixed trigger in a rounded guard, the Patersons used a folding trigger. It only deploys when the hammer is cocked. Not a design that survived long in the development cycle.

The Patent Arms Manufacturing Company produced about 2,500 Paterson revolvers, between the original .28 caliber, and the .36, introduced in 1839. They also made some revolving rifles and shotguns.

The road to success was not smooth, largely due to the Militia Act of 1808, which stated that for purposes of uniformity, the state militias were not permitted to purchase any arms not already in service with the national forces. They could not buy foreign weapons, or in the case of Mr. Colt’s new pistol, experimental ones. Thus he found himself stymied. A few went to the Seminole War, and made a good accounting of themselves. Then in the wake of the “Great Raid” of 1840, Sam Houston tasked a Captain of Texas Rangers, named Jack “Coffee” Hays to contain the Commanche and prevent any more such raids. He armed his company with all the revolvers he could get.

In 1841 (or possibly 1843, sources differ,) at Bandera Pass, the newfangled repeating pistol proved its worth. Fifty Rangers met an estimated three hundred or more Commanche, some of the best guerrilla and light cavalry fighters in the world at that time. His response? “Dismount and tie them horses, boys. We can whip ‘em, no doubt.” With the help of Mr Colt’s revolvers and their five to one firepower advantage, the Rangers held all that day. When the Commanche withdrew that evening, the tide of the Indian Wars in Texas had turned.

Captain Hays sent another Ranger, Samuel Walker, (yes, Walker, a Texas Ranger,) to go find Sam Colt, and buy more revolvers. They were going to need them. When Walker got to New Jersey, however, the Patent Arms Manufacturing Company was out of business. Still, he found Sam Colt in New York and placed an order for 1,000 pistols, with a few improvements. Check back next week for the story of those improvements, the famous Walker Colt.

The Paterson also starred as the villainous Captain Love's sidearm in The Mask of Zorro starring Antonio Banderas and a breathtakingly beautiful Catherine Zeta-Jones.

Awesome report, Jesse. Before he fought off that eldritch horror in Indianola, I can picture Texas Ranger Samson (Sam) McIntyre bringing a pair of Patterson to the fight with the Comanche. 🙂

I'd love to read these together with short stories of characters putting the firearms to good use someday. 👍