Smith & Wesson Model 3914

Howdy, folks, and welcome back to another Tale of a Gun. If you read the series of articles a few weeks ago about trigger systems, you may have noticed that a good deal of the commentary centered around the late, lamented Smith & Wesson metal framed automatics. This is a series of guns I had largely ignored, so my brilliant responses tended to consist of “Uhhhh… I dunno?”

So, I decided to pick one up for testing purposes. Here is my first look at my sample of the third generation of Smith & Wesson auto-loaders, the 3914, along with, of course, a bit of backstory. Consulting the wonderful Lucky Gunner S&W decoding chart, that breaks down as follows. 3914: part of the 3900 series of single stack 9MMs. 3914: the 1 indicates that it’s a compact model, with a DA/SA trigger. 3914: the 4 indicates a blued steel slide. Ordinarily, this model would have a blue anodized aluminum frame, but this one is left natural, for a two-tone effect.

This gun itself is only part of the story, it has some interesting antecedents, but I’ve hit some significant challenges in researching them. It’s an odd story, and not very much of it is documented online. I’ve seen forum posts summarizing various history books, but the best of the books is out of print and now commands extortionate prices online. I’ll give you the story as best I can, but if anyone has one of the books in question, or another that details the story, I’d be grateful for a look, or a few scans, or even to buy it from you if you weren’t set on funding your retirement account with the sale.

Book I’m looking for:

“US Military Automatic Pistols, Volume 3/ 1945-2012” by Edward Scott Meadows

Anyway, the story to the best of my information: During the post WWII re-ordering of the world, with a pivot away from fighting the Axis and towards containing the Soviets, there was a push to standardize ammunition across the nascent NATO. There was a push from the Europeans, along with a vocal minority of the US general staff, to move long guns to an intermediate caliber, and pistols to something smaller than the Americans’ preferred horse-killing .45. Prior to this, many European agencies issued sidearms in calibers like .32 or .380 ACP, a bridge too far for the Americans.

A compromise was reached with the German-derived 9MM Parabellum, aka 9MM Luger, aka 9x19MM. Germany was to be one of the cornerstones of the new alliance, and they already had quite a few weapons in 9MM extant. (Gee, where did all those come from? *Innocent whistling*)

Thus the US military, in 1947 issued a call for submissions for a new service pistol, to be chambered in 9x19MM. It should have no more than a 4” barrel, weigh no more than 25 oz, and hold at least eight rounds. It was not required to be double action, but in the “comparable to” section, the Walther P38 was prominently mentioned.

Several guns were submitted, including an entry from Colt, a shortened 1911 with an aluminum frame and chambered in 9MM, variants on the Browning Hi-Power submitted by both Canada’s Inglis, and FN in Belgium. A very unusual entry was the T3, from High Standard. This was a straight blowback action, which when combined with the alloy frame required to make weight was… rather unsuccessful.

Where’s the S&W in that list? Smith intitially decided not to even bother working something up. It wasn’t until fairly late in the testing cycle that a change in S&W’s management prompted them to get off their collective duffs. One imagines “We lose 100% of the trials we don’t enter,” or words to that effect being uttered in the boardroom.

Circa 1952, several years into the process, their engineers came up with an interesting design, then dubbed simply “The 9MM.” Quite honestly, it looks like the sort of thing you’d get if a P38 and a 1911 loved each other very much. The slide, complete with barrel bushing, looks very 1911. The trigger system is very similar to the P38, though with an improved pull weight. It had a single stack 9MM magazine, and an aluminum frame.

What the Small Arms Board would ever have made between the proto-Colt Commander and the proto-Model 39 is a question for the ages. (And of course, the stuff of gun magazine shootouts for the next few decades.) Two factors seem to have been in play. Just about this time, there was a conflict in Korea.

As I touched on in the articles about the M14 and the Assault Rifle Revolution, commanders there reported significant issues with stopping power, trying to stop the massed human wave attacks, even using manly calibers like the .30-06 and .45 ACP. Interest in switching to smaller cartridges to appease effete Europeans, (even if it meant each man could carry a lot more rounds,) cooled rapidly.

The second element was that the pistol just wasn’t that important a war-fighting tool. They already had 2.5 million 1911s and 1911A1s in stores. Re-equipping with a less powerful round just didn’t seem like a priority. (Wait, this doesn’t sound like the US Government we all know and love. Was this a breakout of common sense? In Washington? I know. It’s shocking. Somebody, please find me that book!)

Anyhow, the plug was pulled, and the 1954 US Pistol Trials withered with no clear winner. The 1911 would soldier on for another 30 years before eventually being replaced by another double action single action 9 mm, the M9 Beretta. High Standard apparently just shelved their design, but both Colt and Smith decided their entries were marketable. Thus were born the Colt Commander, (later to be available in .45 ACP as well, and in the ‘70s, when they released the steel framed Combat Commander, the original aluminum version became the “Lightweight Commander.”)

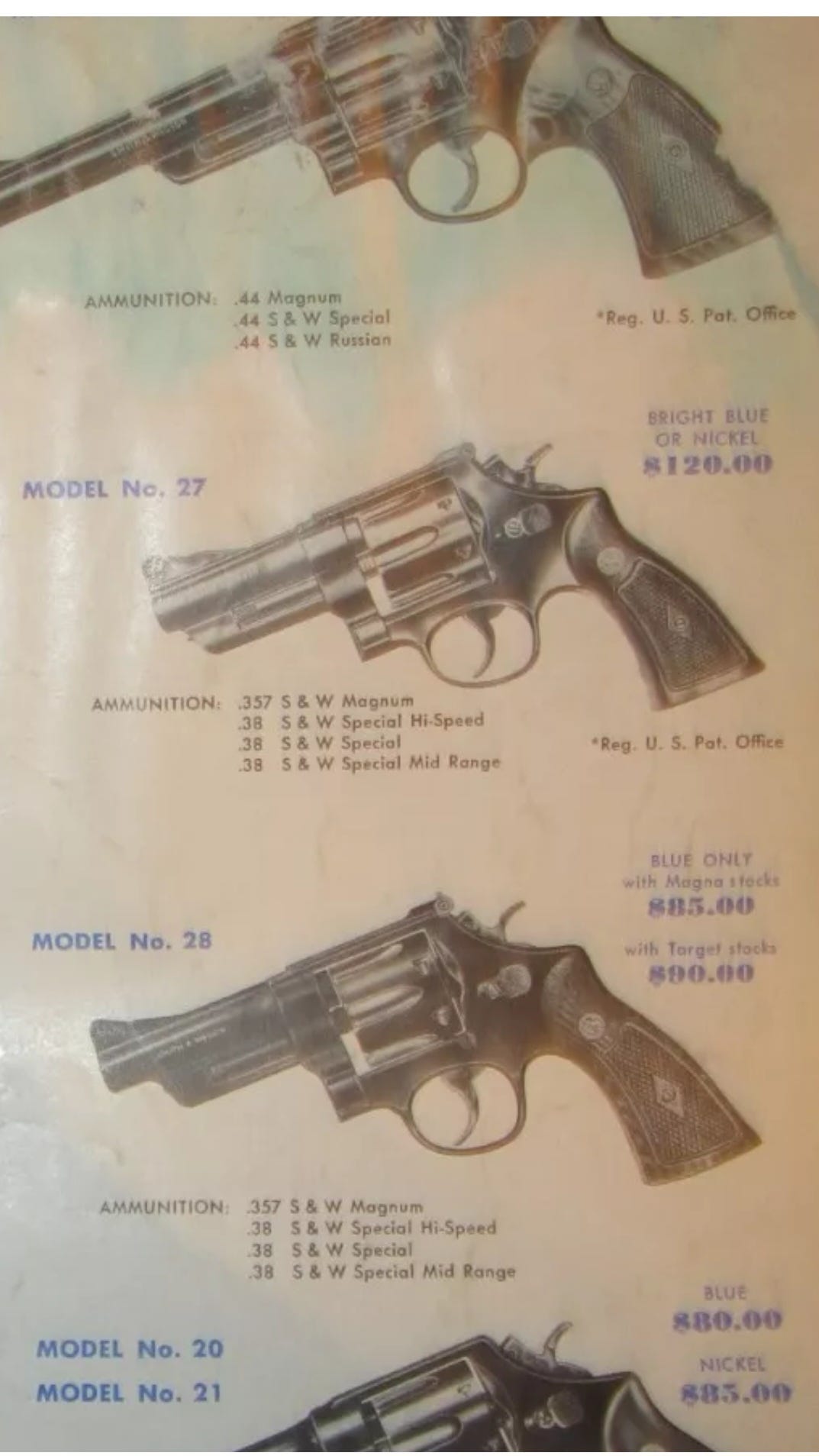

Smith & Wesson released their pistol as “The 9MM.” A year or so later, they switched their whole line from richly evocative model names to a more or less sequential numbering system. Right after the Model 38, formerly the Airweight Bodyguard, came the Model 39, formerly known as “The 9MM.” By 1959, it was only available in blue, cataloged for $75, only a smidge higher than the ubiquitous Model 10, (formerly the Military & Police) at $65 for blue, $70 for nickel. Ten dollars cheaper than the Model 28, the Highway Patrolman, and much cheaper than the flagship “.357 Magnum,” the Model 27, which cost a princely $120 in bright blue or nickel.

Still, in the civilian world the revolver was king. No new-fangled auto-loaders need apply. The first cracks in the dam began to appear in 1967, when the Model 39 was adopted by the Illinois State Police.

A second S&W auto came about when the US Navy asked S&W for a higher capacity version of the Model 39, one that would accept the 13 round magazine of the Browning Hi-Power. In the end, they developed their own 14 round magazine. Again, the pistol wasn’t purchased by the military, but also again it was released commercially, this time as the Model 59. The newer, higher capacity model, the beginning of the wonder-nine revolution, began to make great inroads in the law-enforcement market.

The civilian defensive market was lagging behind. By the 1970s, if you wanted to carry a full-power service cartridge, the only real options were a full sized service pistol, or a J-frame revolver. A compact auto was by definition in one of the compact cartridges, .25, .32, or .380 ACP.

The ingenuity of the American gunsmith will not be denied. If there is a paying market to be exploited and the big companies leave an opening, someone is likely to offer a solution. In this case, two notable solutions were Paris Theodore’s ASP pistol, derived from the Model 39, and the Devel Full House Custom, a much shortened Model 59.

When Smith and Wesson finally took notice they began including compact models in their second generation lineup in the early 1980s.

The second gen only ran for a few years before the third gen debuted in 1988. Those were the guns, (there were a bunch of them. From the two basic models of the first gen, now we see single stack, double stack, multiple calibers, multiple sizes, blued finish, stainless, aluminum frames, steel frames, DA/SA, DAO, decocker/safety on the slide, decocker only on the frame and lots of the potential combinations thereof,) that finally completed the transition from the revolver to the semi-auto for law enforcement. Through the 1990s, the S&W pistols were everywhere.

The fly in the ointment was that as robust and reliable as they are, all that high quality machining came at a price. By the end of the third gen's run in 1999, the full-size double stack 5900 series started at $663, and ran up to $841, for a stainless frame and night sights. In 1999 dollars. About $1,550 today.

This was the gun that Glock killed. Into this market came the plastic Austrian. They offered a uniquely simplified action system that required little fitting, and the polymer frame could be produced for pennies. In 1999, the Glock 17 retailed for around $450, and they offered steep discounts on agency purchases. Smith & Wesson couldn't compete with that pricing, and eventually discontinued the entire lineup, to be replaced with the abysmal Sigma series. Those guns were so close to the Glock that they won Smith & Wesson a cease and desist order. In the late oughties S&W finally settled on the polymer frame M&P series as their auto pistol of the future.

So, what do I think of my little sample?

It’s an interesting gun. Both to compare against the guns that went before it, like the 1911 and Hi-Power and P38, and how far the industry has come since.

The 1911 is a 5” barrel, with a 3-finger plus grip. In the traditional steel frame it weighs around 40 oz. This is a 3.5” bbl, with a two-finger grip. It’s a lot lighter at 25 oz, but both carry 8+1. My example has fat rubber Hogue grips. With them on, it actually feels fatter than the 1911, which is hilarious.

A good duty trigger in a 1911 should be around 4 lbs. This one is DA/SA. The DA first shot is around 12, of course, which is to be expected. The SA pull, though, is surprisingly heavy. There’s considerable takeup, like a two-stage trigger. Once it hits the wall, the break is crisp, but most I’ve seen measured around the ‘net place it at 6-7 lbs. I’d say this one is every bit of that.

In casual shooting the first day , it seemed extremely accurate, but I was goofing around too much to get a solid group. The next day, with publication looming I was sure I could just walk out back and post up a brag worthy group. I’ve heard that hubris leads to a fall, but it’s possible that the 7 lb trigger, 95 degree day, breezy conditions, and my junior model range-masters (I had to stop shooting several times to defuse a potential fight over who had custody of Barbie and her shoes,) had something to do with it. Enough excuses, however. Out of five or six tries, this was the best I managed. Let’s just say the rest were worse.

Modern compact nines have come a long way. This single stack model probably made sense in the context of the Clinton Ban years. Why buy a bulkier double stack gun, if you couldn’t buy the mags for it? Today? It’s certainly viable. It’s a solid shooter. The trigger could be lighter, and I’d like to see how it is with slimmer grips, but it’s quite tame for a more-or-less compact nine. I’m interested to play with the double stack equivalent, a 6904 or 6906, sometime. But you just can’t deny that something like the P365 or G43x is smaller, lighter, and carries 1.5-2x the ammunition, depending on the magazine.

I liked the 3rd generation Smith’s. Some like my 4506 were a bit heavy, dad had a 5906 and a 4006. We liked them.

I owned a 3913 in the ‘90s. I wish that I still had it. I was a young man with a family and probably had to pawn it off to make ends meet. Great article. I’m now a Glock guy. :)