Savage 340D

Wait, you say. That’s not an AR-15. You said it would be the AR-15 this week!

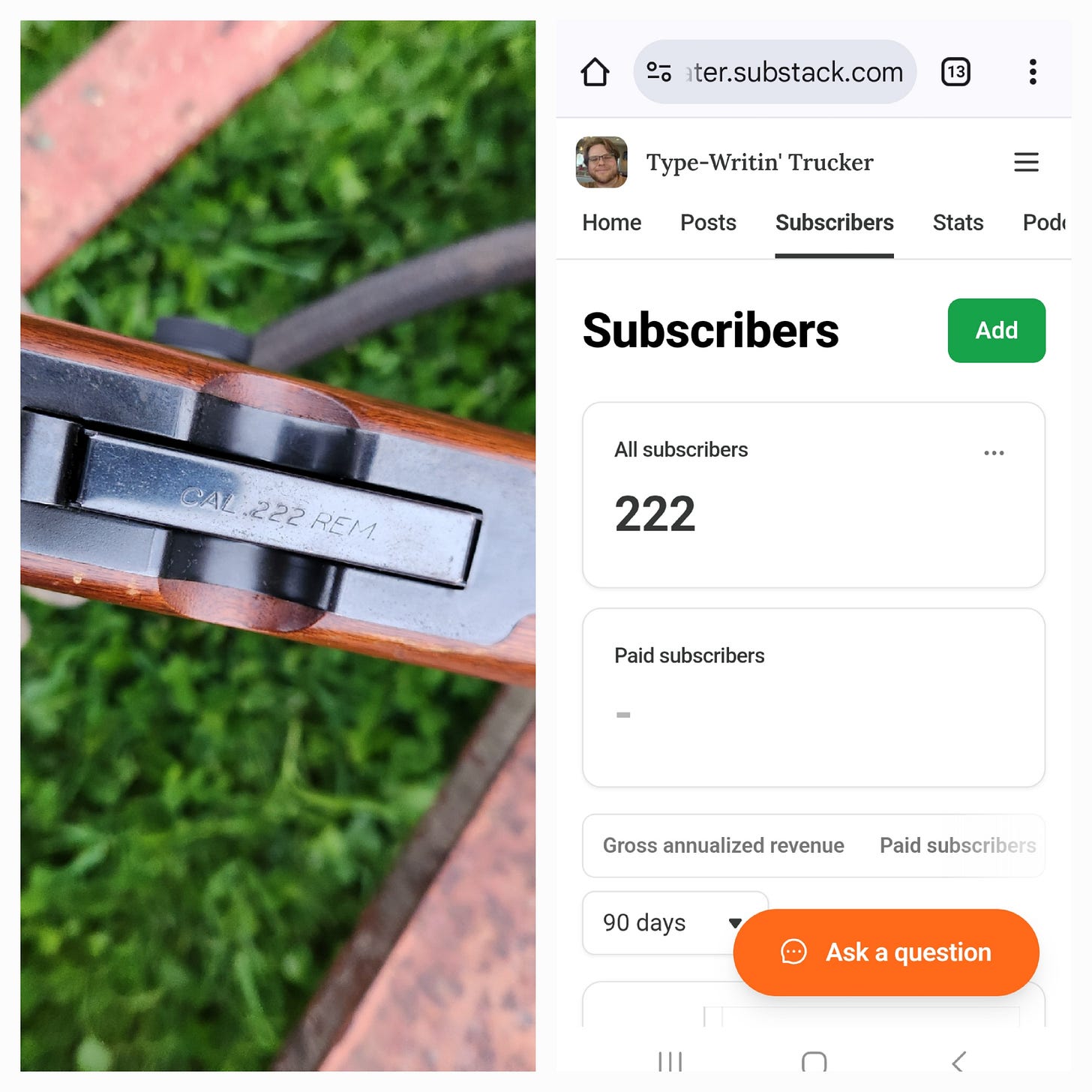

So I did. Good catch. However, this is the special Subscriber Appreciation Post. You see, this week we hit 222 subscribers here on Type-Writin’ Trucker. For everyone who has signed up to read my gun rambling and my noir scribblings, I thank you profusely and profoundly. In recognition of the 222 milestone, (and partly because I just had it out,) this week we’re going to look at my Savage 340D, in .222 Remington. The Triple Deuce.

.222 Remington? I thought it was .223? The .222 is the older cartridge, from which the now ubiquitous .223 derives. Let’s dive in and take a look.

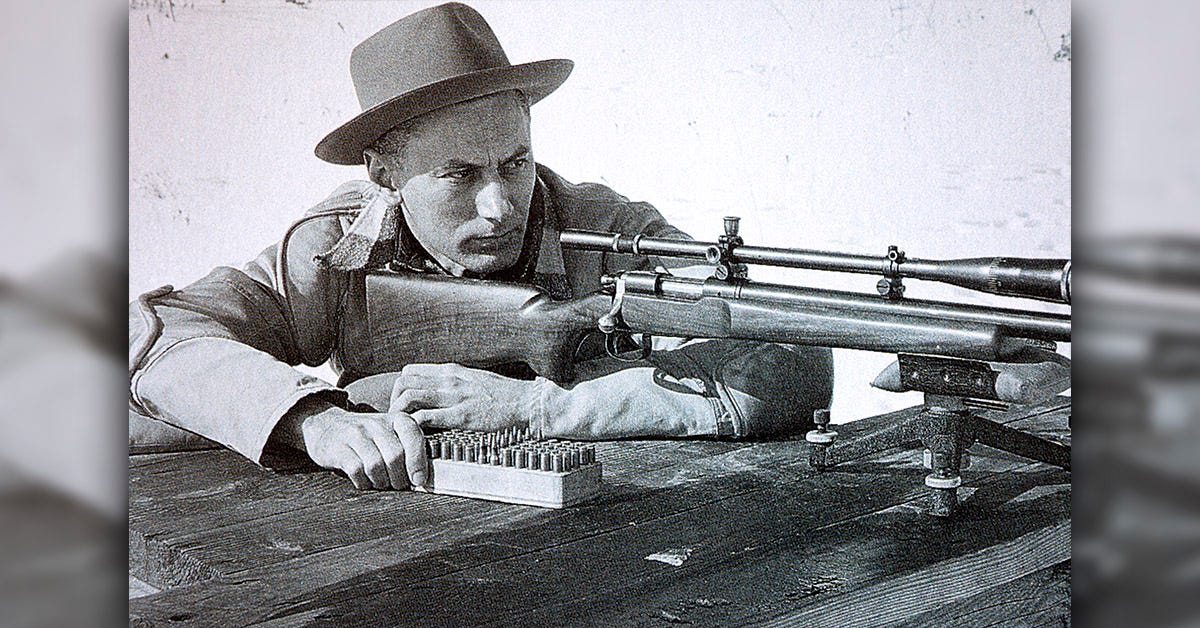

A varmint and target cartridge developed in 1950 by Remington engineer and avid bench rest competitor Mike Walker, the .222 Remington was the first rimless .22 caliber cartridge developed in the United States. It’s that rarity of things in cartridge design, an entirely new case. It made its debut in the Remington 722 rifle, a precursor to the now-famous Model 700.

There had been several extremely high performing .22 caliber centerfires around since the ‘30s. The .22-250, so named for being a .250-3000 Savage case necked down, and the famous .220 Swift, the first factory cartridge to send a bullet over 4,000 feet per second. For maximum impact on target, those are both excellent, but they achieve their results...violently.

Both are extremely loud. Both, though especially the Swift have a reputation for burning out barrels. Especially with long strings of fire from a heated barrel, a Swift could be “shot out” in as little as 3-400 rounds. When the action gets hot and heavy at a prairie dog colony, that could be a single afternoon’s shooting. Depressing.

In addition to the wear and tear on the eardrums and equipment, the max-speed cartridges burn an awful lot of powder their miracles to perform. The .22-250 typically burns 35-38 grains per shot, and the Swift up to 45.

Mike Walker decided it was time for a kinder, gentler, more efficient cartridge, and that’s what he set out to develop. The new case used the modern method, and headspaced on the shoulder, rather than the big, clunky rim of the Swift. The case was much smaller, too. The Triple Deuce does its work on a mere 23-25 grains of powder, close to half the bill presented by the big Swift, yet still hits velocities in the 3,200-3,400 range. 85% of the performance for a shade over 50% of the powder. The increase in barrel life was still greater. When Mike Walker’s personal .222 was sold a few years ago, it still had the original barrel, even after 40 years of enthusiastic shooting.

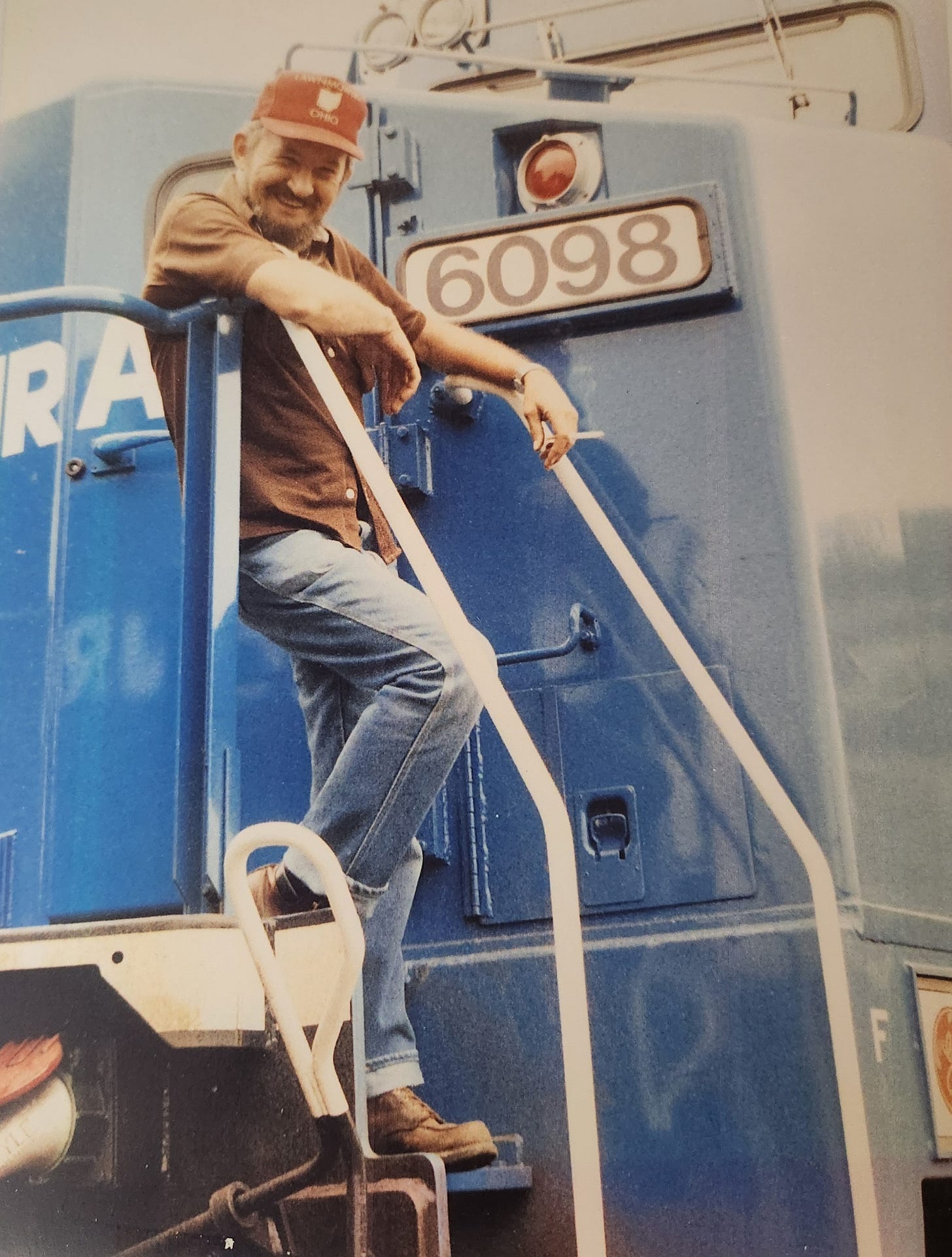

That economical nature, in addition to the sterling reputation for accuracy won in benchrest competition helped to sell rifles. Just like NASCAR, what wins on Sunday sells on Monday. Not only Remington rifles benefited, but other companies as well. .222 Remington became one of the better sellers in Savage’s 340 line of rifles. More economical and less refined than the Remingtons and Winchesters of the day, Savage (and their twins, the Stevens,) were working men’s guns, often as not sold in hardware stores, not only sporting goods houses.

One such working man was my grandfather. He liked to hunt and shoot, but opportunities for it were few in those days of whitetail populations on the edge of extinction and rigidly controlled seasons. To keep himself in practice the rest of the year, he took to varmint hunting, especially groundhogs.

Groundhogs are essentially chubbily overgrown ground squirrels. To a person who only sees them in the median strip of the highway, or on television from Punxatawney, they can seem inoffensive, even cute. To a farmer they can be a nuisance. They burrow, and their burrows are often not all that deep. An unsuspecting cow or horse can easily fall through the thin roof of a burrow and break a leg. I’ve nearly come to grief that way myself. They can undermine buildings. Even farm equipment can fall victim to their holes, breaking steering gear or even drive axles. Thus farmers, who may be reticent about giving permission to hunt their deer, are often eager for someone to shoot their groundhogs.

That’s what the Savage excelled at. He had a friend reload his brass for him, so he could keep shooting for pennies. It’s a rifle you don’t get tired of shooting, and the neighbors don’t get so tired of hearing.

A number of things about the way the old Savage is built strike the modern eye as strange. These guns weren’t built with optics in mind, so mounting a scope was a job for a machine shop. The barrel is held down with a band, rather than free floated in the modern way. There’s only one screw mounting the action into the stock, and no bedding compound or metal pillars in sight. The trigger is passable, probably four or five pounds, but a far cry from today’s Accu-Triggers or Timney specials. As one older gent once told me, “the .222 may be famous for accuracy, but not that one.”

Still, while it may not produce the bench rest competitor’s quarter inch groups at a hundred yards, it’s more than adequate. With careful attention from the torque wrench screwdriver, it puts three rounds into an inch to an inch and a half.

When I inherited it, it was wearing a fixed 6x scope. The glass was pretty well fogged, so I replaced it with this 6-18x baby Hubble. I learned an important lesson about magnification. It magnifies the wobbles and the shakes, as well as the target. I find I do much better shooting if I just leave it at, you guessed it, 6x.

Now that I’ve got my own home place, I find I have no love for groundhogs, either. The other night I was helping out in the kitchen and chanced to look out by the barns just in time to see chubby Mr Groundhog waddling out from under. I grabbed the Triple Deuce from the safe, popped in the loaded magazine and walked out to the porch. It was only 90 yards, small potatoes for a rifle like this. I settled the crosshairs and squeezed off the shot. When I threw the bolt, I spotted two rabbits hopping around. Targets of opportunity. Three for three, in about twenty seconds. Not too shabby for an obsolete cartridge in a hardware store bolt gun.

Now, if you’d like to see a similar subscriber tribute to...say...the .375 H&H, then share this Substack with someone you think would appreciate it. (And maybe buy lots of books, so I can afford one.)

In all seriousness, thank you everybody. Next week, the AR-15 for sure.

Speaking of hardware store guns, the Ace Hardware in my small town sells guns and donuts from the same counter. Almost heaven. https://www.ar15.com/forums/General/How-did-I-not-know-about-the-doughnut-gun-store-/5-2790426/

Congratulations on 222. I’ve been using the bolt action 16 ga western auto hardware store toob on ground hogs. My ranges are much shorter here. Great piece!