Remington Model 11

“Look! It’s a humpback Browning! Must be an Auto-5!”

“Nope, it’s a Remington Model 11.”

“What? That’s not an 1100. It’s obviously a Browning!”

*Actual text of conversation, almost every time I get this gun out.

Howdy, folks, and welcome to another Tale of a Gun. Sorry for the late release, I’ve been copy-editing “Wyrd Warfare,” forthcoming from Raconteur Press. It sort of sucked all the air out of the room. Or at least my brain. Wait, did I just admit to being an airhead?

Ahem. Back to the gun.

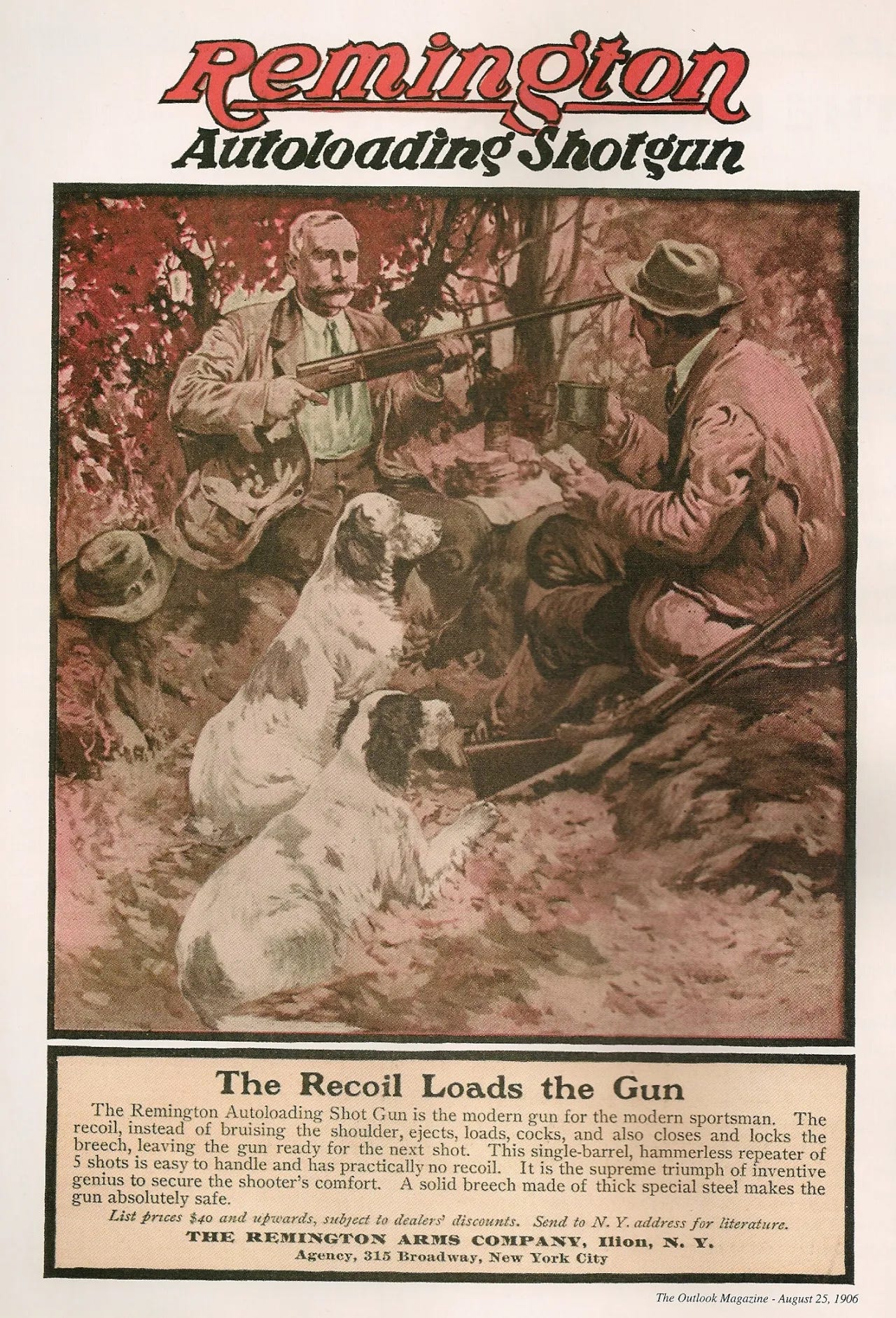

Yes this is, in fact, a Remington. From 1905 until 1949, Remington actually produced the John Browning design under license, here in the US. The “Browning” guns were, of course, made by Fabrique Nationale, in Herstal, Belgium.

And yes, they called it the Model 11, which isn’t at all confusing when later model which became famous for them was the 1100.

Let’s dig in, shall we? First off, what is the Browning Auto-5?

It’s the first production semi-auto shotgun in the world. Designed in 1898 by none other than the prolific firearms genius, John Moses Browning. This just a few years after he designed the first really functional repeating shotgun, the Winchester 1887, and the first good pump shotgun, the Winchester 1893/1897.

And it’s a truly monumental feat of engineering. It stood as the world standard in semi-auto shotguns for the next fifty years, and stayed in production for nearly a hundred.

What makes shotguns so complicated? After all, it’s just a smooth piece of pipe, right? None of that rifling stuff to fool with…

Well, you’d think so. The trouble really comes from the ammunition. Shotgun ammunition comes in a ridiculous profusion of variations. Different shot sizes, different power levels, different manufacturers all marching to their own case-dimension drum… and yet a semi-auto has to somehow be able to compensate for all these wild variables. This challenges designers even today. Most semi-autos will really only run well on a diet of shells they like, within a fairly narrow power level band. Too soft and they won’t cycle, too heavy and the power will beat up the action.

So how did John Browning design one that not only worked, but could accommodate a broad range of ammunition, and do it five quarters of a century ago? First, it’s a long-recoil system, meaning that barrel, bolt and all recoil together the full distance. This is truly strange to modern eyes, seeing the barrel reciprocate with every shot. The barrel unlocks from the bolt at full rearward travel, and is propelled forward by a big honkin’ spring. The bolt stays to the rear, with the extractor holding the fired shell in place. Once the chamber has cleared the shell, (backwards from how we usually think of extraction, but it’s the piece that’s moving,) the shell is ejected from the right side, and the bolt starts forward, picking up a new shell from the magazine on the way.

The brilliance of this design is that it’s adjustable. Take off the barrel and forend, and this is what you find. The aforementioned big honkin’ spring, which looks like something out of a car’s suspension, and some random little ring thingies.

Those rings are the friction rings. They are squeezed against the magazine tube, thus controlling the speed of the recoiling action. Set up one way, they grip quite tightly, thus slowing things down for heavy hunting loads. Set another, they hardly grip at all. The gun can then cycle, even with light target loads.

Of course, they do have to be set correctly, which takes a bit of tinkering by the owner. In a prior age, when automotive owners manuals specified things like spark plug gap, how to set the points and adjust the valves, this wasn’t considered particularly onerous. Nowadays, when those manuals have to specify “Don’t drink the battery acid!” that may be relying too much on the user for the lawyers and warranty department’s comfort. Thus, the race is on for that magic shotgun that will somehow self-adjust between powder-puff target ammo and heavy duck and buckshot loads. The long-recoil system’s greatest strength is also its greatest weakness.

Okay, so that’s the Auto-5. What’s this Remington business?

Well, when Browning first designed the gun in 1898, he first took it to Winchester, to whom he’d sold all his previous rifles and shotguns. Versions vary as to what happened there. I’ve read that Winchester were unhappy with how the project for the 1893 went, which required significant reworking to turn into the 1897. I’ve read that Browning knew he had something good on his hands, and didn’t want to just sell the design for a flat fee, as he had in the past, but rather wanted a per-copy royalty, which Winchester didn’t want to pay. Either way, the deal wasn’t made.

Browning took the gun to Remington, but the president of the company had a heart attack while Browning was waiting to see him. That complicated their acquisitions process for a good long time. Somehow, Browning wound up at FN, in Belgium. They’d already built some of his pistol designs, and knew one another. A deal was struck, and Browning Auto-5s began rolling off the line in 1902. Beautiful guns, nearly all.

By 1905 Remington had its house in order, and realized what a good thing they had missed. They wound up licensing the design themselves, and produced it as the Remington Model 11. The only real differences between the two are that Browning had a magazine cutoff feature which the Remington did not include, and that most Browning models were higher grade, and most Remingtons were more workmanlike. Ironically, during WWII production of the Browning guns—complete with mag-cutoff switches—moved to Remington while Belgium had other things on its mind.

Remington produced the Model 11 through 1949, when it was replaced by the 11-48, which was still a long recoil action, but cheaper to build with its stamped steel parts, and featured a more streamlined look than the old humpback. In 1963, the 11-48 was replaced by the 1100, which kept the sleek look, but was a revolutionary change inside, being gas operated.

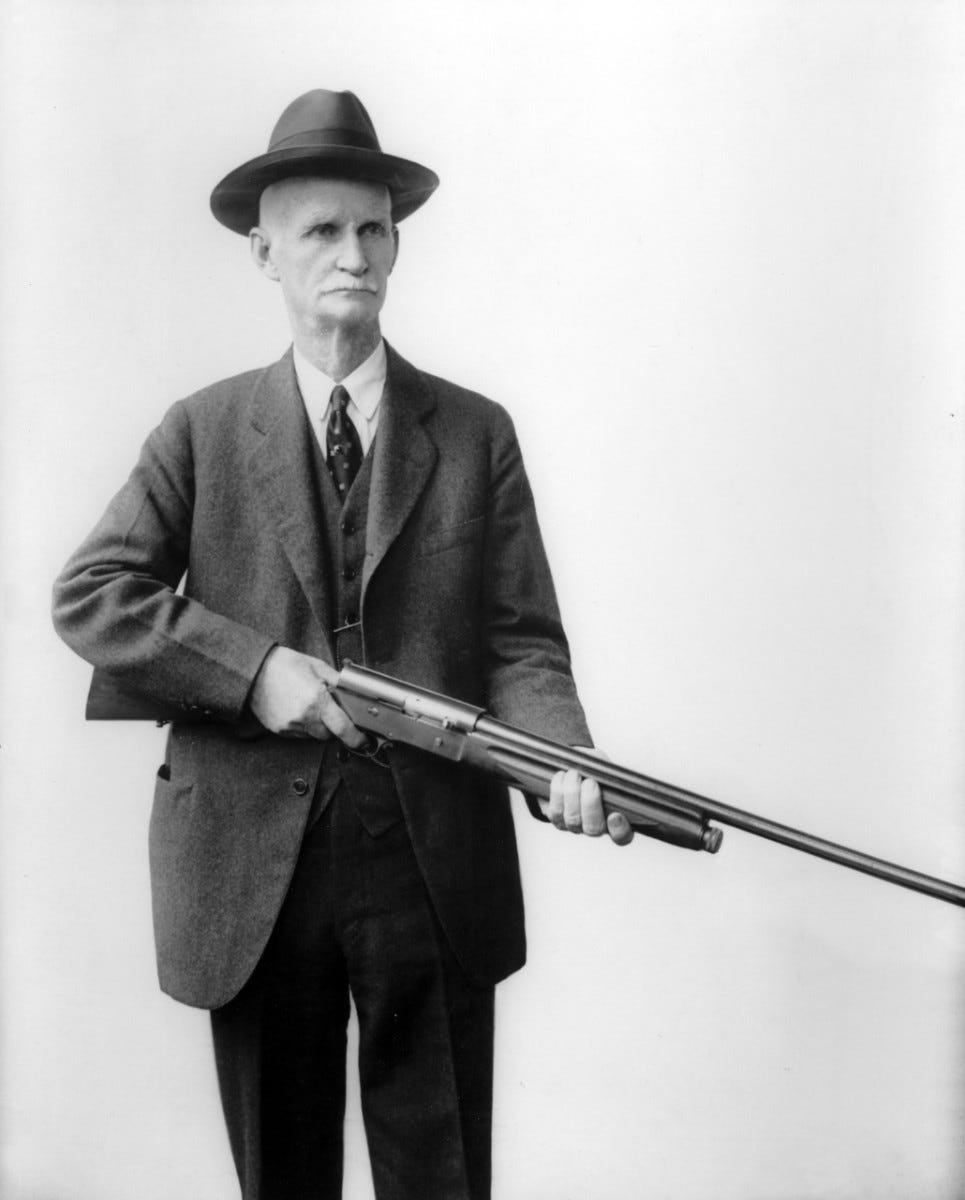

My particular example is a 1920s production plain jane hunting gun, which has probably lived a hard life. There’s not much finish left on the metal, and somebody decided to re-do the wood, not much to their credit. I picked it up at a gun show for $100 even, back before old guns started going through the roof.

An interesting feature of the earlier guns is that the safety switch is a sliding unit, inside the trigger guard. This arrangement would later be used on the M1 Garand, as well as the derived M-14 and Mini-14. It gives modern safety komissars conniptions when someone has to reach INSIDE THE TRIGGER GUARD to actuate the safety.

How does it shoot? It’s not as soft as a gas gun, nor as rough as the modern inertial actions. It has a sort of “double shuffle” to the recoil impulse. Just like the looks, some people love it, some people hate it. Personally, I love it. I love the clockwork/steampunk aesthetic. The reciprocating barrel, the extra demands the adjustable system requires of the shooter, all of it. The only real complaint I have is that it’s not light. For sitting in a duck blind, or under a tree waiting for squirrels, it’s not bad at all. For tromping around all day behind an upland dog, I’d probably pick something lighter. A Belgian Light 20, for example.

The man really was a genius. Ive never had an Auto 5 or a 11, but my first firearm was a HiPower clone, and dispite some atiquated features it was a great pistol to learn on.

Purchased my model 11 in the early 80’s for $75. Still got it. Full choke.