M16

Howdy folks and welcome back. Today it’s (arguably) the king of the assault rifles, the M16. Like we talked about last week, it wasn’t the first. That honor goes to the StG 44.

Anyone who’s used to traditional rifle designs and sees one of Eugene Stoner’s babies is likely to be outraged. The Army brass who rejected the original AR-10 certainly were. At first glance, and often at second and third glance, it seems like an outlandish contraption. But each of those outrageous features has a purpose. Performance.

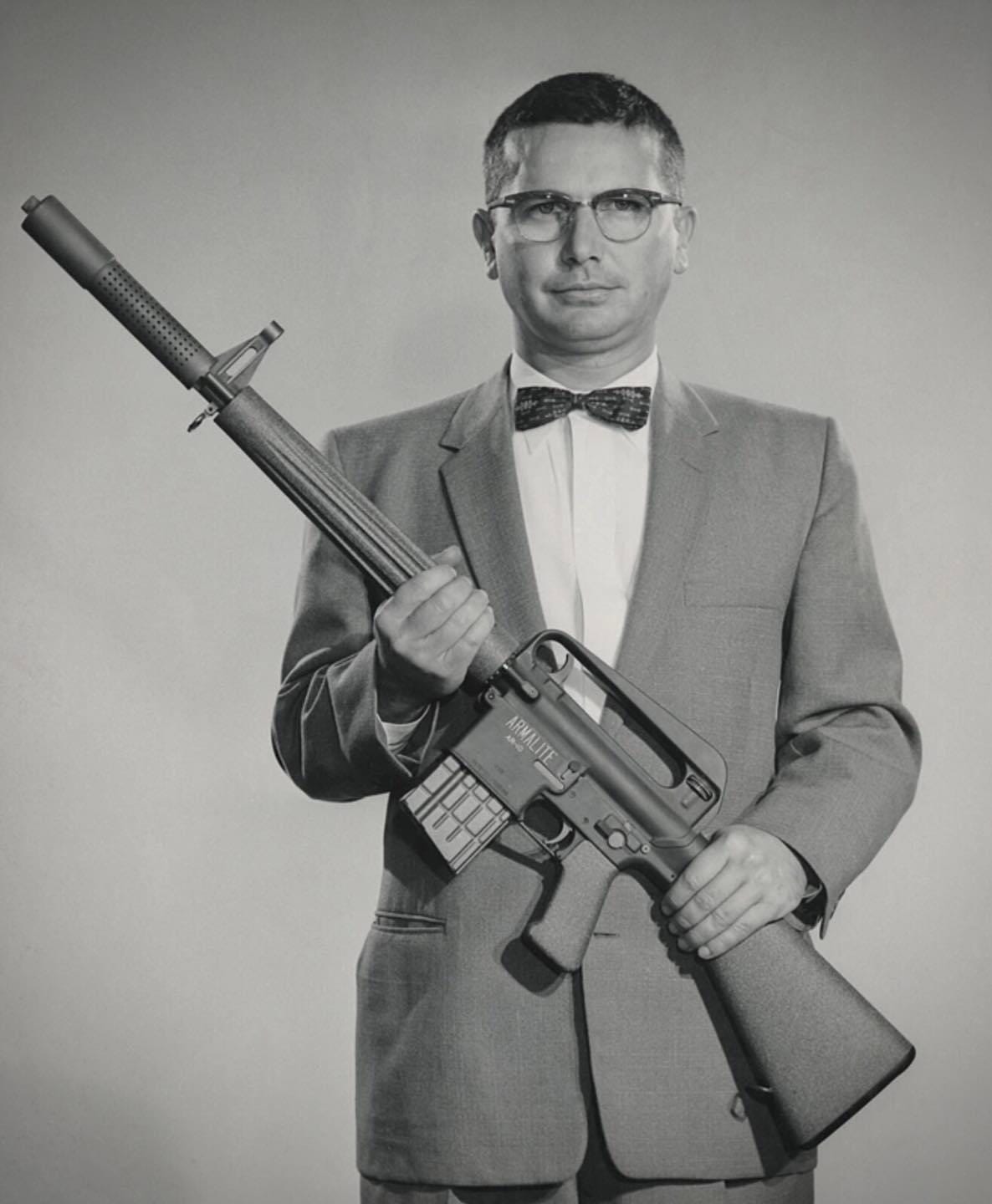

The story of the AR-15/M16 family begins with a company called ArmaLite, which was a subsidiary of Fairchild Aircraft, (creators of the C-119 Flying Boxcar, and later the A-10 Warthog.) Being an aircraft company, they had seen the transition from wood and canvas airplanes to modern aluminum, and they thought that a similar revolution was in store for small arms.

In 1954 they hired Eugene Stoner to be their design chief. Stoner had been an aviation machinist before WWII, and when war came he enlisted in the Marines as an Aviation Ordnanceman. He worked in the South Pacific and northern China, often as armorer for heavy aircraft machine guns.

Thus, he knew intimately well how full-auto worked, and was comfortable with advanced materials. Applying that knowledge to the wood-and-steel world of the 1940s battle rifle set the world on its ear.

He designed a number of rifles for ArmaLite such as the AR-3, AR-5, (which actually got picked up as a survival rifle for the military,) AR-9, but his most significant work was on the AR-10. Incidentally, with all these ARs it should be noted that it stands for “ArmaLite Rifle,” not “Automatic Rifle,” or “Assault Rifle.” The AR-5 is certainly neither, but it is still an AR.

The AR-10 was designed for the Army’s new service rifle trial, the one that ultimately became the showdown between the M14 and the FAL. It’s deeply ironic, given that later experience with the M-14 showed it was “functionally useless in full-auto,” but the AR-10 was built with full-auto controllability as its main goal. It was too new, too bizarre, and arrived too late in the process to get a fair shake. As we discussed in the M14 article, the folks at the Springfield Armory had their thumbs pretty firmly on the scale anyway.

How did it accomplish this controllability? Especially since it weighs two-and-a-half pounds less than the M14? The first was to separate the sighting plane from line of the bore. For most of the history of shoulder-fired firearms, the goal had been to have as small an offset as possible, to make for easier sighting. That always required the barrel mounted higher than the stock, to be close to the line of sight. The line of recoil was moving back, but out of line with the resisting force. The gun would pivot around the shoulder a bit, causing it to rise in recoil. With a single shot or even a repeater, this didn’t cause any great trouble. If anything, those earlier shooters probably appreciated it, as force that went into raising the rifle didn’t go into beating up their shoulder.

The move to shoulder-fired full-auto changed all that. No longer was there time to recover from recoil before taking the next shot. Not with a cyclic rate north of 700 rounds per minute, as most of the battle rifles had. That’s 11 or 12 rounds per second. Thus, even a tame, light kicking little rifle like the M1 Carbine, in its guise as the fully-automatic M2, had a tendency to become an anti-aircraft gun after the first few rounds in a burst. How much more a full powered rifle like the M14?

Stoner realized this from his work with aircraft gunnery. When attaching multiple machine guns to lightweight flying machines, the direction of recoil had to be accounted for. A plane could easily become unstable, otherwise.

The other major departure from tradition was in reducing the amount of metal moving around with each shot. In a rifle like the M1 Garand, there is a gas piston, pushing on the operating rod, which pushes on the bolt. Later designs improved on this, like the short stroke piston of the Carbine, or the self metering system of the M14, but the AR-10 did away with the piston entirely. Stoner used a system called “direct impingement,” in which the high pressure gas exits the barrel, travels through a long tube, then affects the bolt and bolt carrier directly. No piston at all in between. He decided that a charging handle flopping back and forth with the bolt, like all the Garand-based designs had, was foolish.

With straight line recoil and far lower reciprocating mass, the AR-10 already had a leg up. With the receiver was made from aircraft grade aluminum and the stock from phenolic resin, it was a rifle for the space age.

It was also a flop. ArmaLite’s president, George Sullivan, had specified an untested aluminum/steel composite barrel for the test, (over Stoner’s protests.) It burst under trial. The Army saw potential in the design, but by 1957 the need to update the Garand was clear. The rest of the world was arming with AK-47s and FALs. They wanted something ready to go, not something still in development. The AR-10 was rejected.

However, General Willard G. Wyman, one of the faction of brass hats in favor of an intermediate cartridge rifle, asked ArmaLite to scale it down. Eugene Stoner and Jim Sullivan At ArmaLite complied, resulting in the .223 Remington chambered AR-15. All the same technology that went into making a full power battle rifle controllable made shooting the new intermediate rifle a breeze. However, a different brass hat, this one Maxwell Taylor, the Army Chief of Staff vetoed the idea. He wanted a traditional heavy-caliber rifle.

ArmaLite, at this point frustrated with the process and suffering financial difficulties, sold both designs to Colt.

With far greater resources, Colt quickly refined the design, changing the charging handle from the odd, upside down trigger arrangement inside the carry handle to its now familiar location at the back of the receiver.

The first few matchups between the M14 and the AK-47, in the early days of the Vietnam war, however, showed a performance gap. The big rifle was too hard to control in full-auto, and soldiers struggled to carry enough ammunition to get fire superiority over AK equipped troops. The M2 Carbine could carry the ammo and was easier to control, but didn’t have the punch at range to compete. At last, the intermediate cartridge faction began to carry the day.

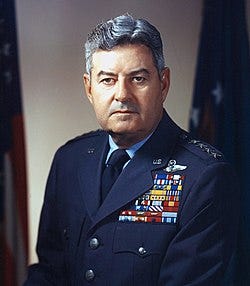

Colt’s first sale of their new rifle was to the Air Force. With all the aircraft design lineage, this might not be as surprising as it first seems. They impressed Curtis LeMay, the man who masterminded the strategic bombing in the Pacific and the Berlin Airlift, and headed SAC after the war. He was, by this time, Deputy Chief of Staff of the Air Force, and he ordered 8,500 of the new rifles for his security troops. Soon, he became Chief of Staff, and wanted to order another 80,000, but the Chief of the Joint Chiefs was old Maxwell Taylor. They took their squabble to Robert MacNamara, the Secretary of Defense, who thought having two rifle calibers across the armed forces was poor logistics. He ordered more testing to decide which should go.

The numbers told the tale. 44% of troops trained on the AR-15 qualified expert, to 21% with the M14. It let a soldier carry three times the ammo for the same weight. It was actually controllable under full auto.

On top of that, the M14, always a complex design to manufacture, was having production issues. The plug was pulled, and the US Rifle, Caliber 5.56 MM, M16 was adopted.

Unfortunately, in the rush to implement the new system, a few things were overlooked. Cleaning kits, for one. The new rifle was billed as “self cleaning.” Given the nature of a direct impingement action, few things could be further from the truth. They also omitted the chrome lined bore, as a cost savings measure. Given the harsh jungle environment, it’s small wonder the new rifle didn’t initially cover itself in glory.

Reliability issues plagued it for much of its early service. Now, my shooting background is civilian competition, not military. Even so, these issues grieve me in a way that’s hard to adequately describe. I know just how heartbreaking it can be when a gun breaks or chokes in a match, when all that’s at stake is a blue ribbon or a belt buckle. How much more so when it’s your life, or your buddies’ lives?

The small caliber, weird design, and spacey materials hardly inspired instant confidence. Over the next six decades, however, they pretty well worked the bugs out. The M16 and its progeny have been the American Service Rifle for an astonishing amount of time. From the jungles of Vietnam to the deserts and door kicking of the Global War on Terror, it has been through a process of iteration and refinement unmatched in the history of firearms. Just as a trooper in Vietnam might find himself carrying the new and improved version of the Garand rifle his father shot Nazis with, it’s not uncommon for a kid in boot camp today to train with the M4 carbine his dad carried in Iraq. His grandfather might have carried an A2 in Kuwait, and his great grandfather an A1 in ‘Nam.

Black plastic and aluminum doesn’t often inspire the same nostalgia that wood and steel do, but the little black rifle that could has seen a considerable slice of history.

Tune back in next week for a look at the civilian side of “America’s Rifle.”

Great stuff. Apparently Sig Sauer has been tapped by the Army for a new battle rifle in a 6mm+ caliber. The most innovative feature seemed to be the ability to fire in three round bursts. Most gunsmiths and military were skeptical of the higher caliber saying it's just more and heavier gear to put on already overloaded infantrymen.

Love building ar’s. Especially when they come out perfect.